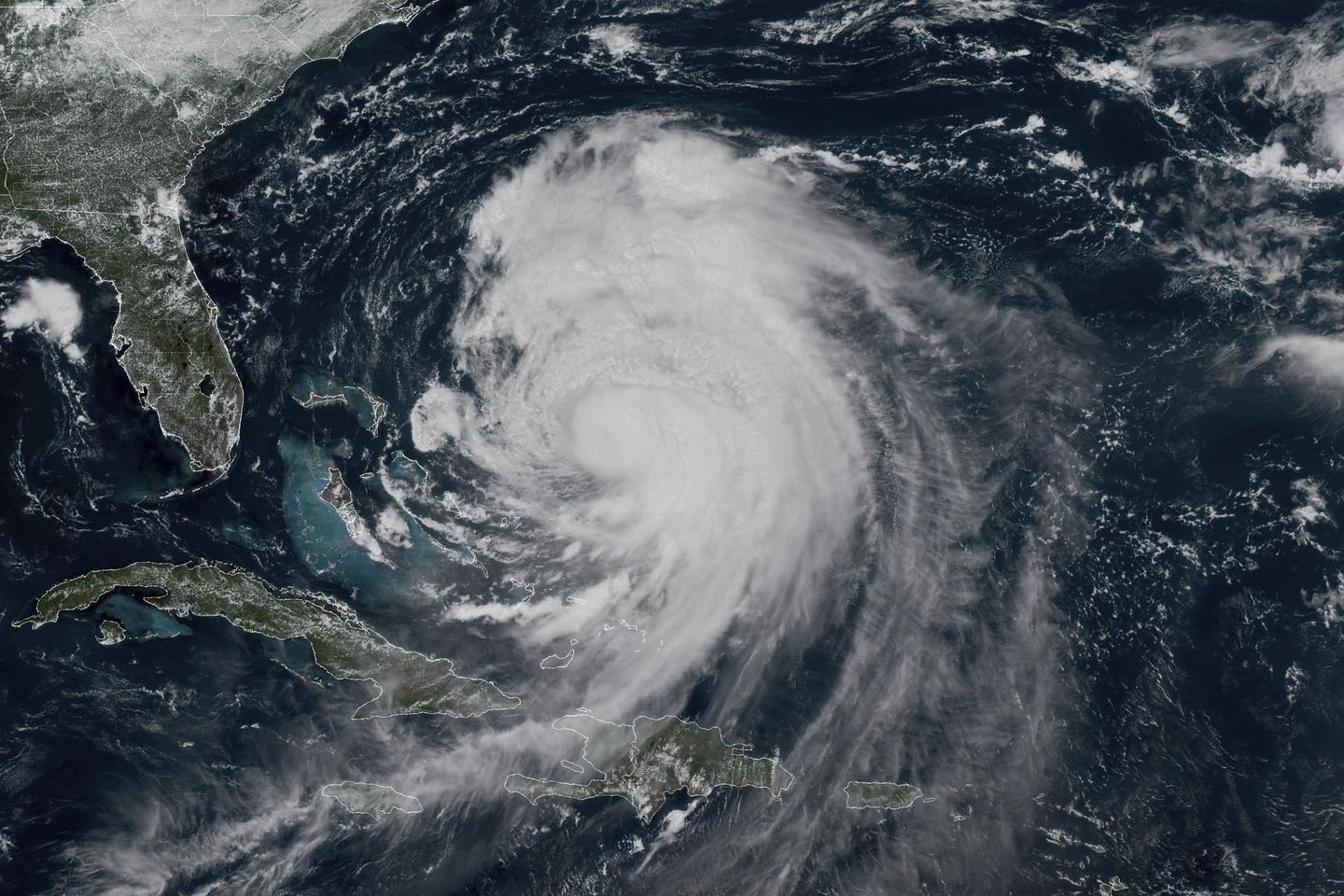

Hurricane Erin is creating potentially deadly water conditions all along the U.S. East Coast days before the largest waves are expected, with high winds and waves anticipated in North Carolina by Wednesday night.

Erin lost some strength Tuesday and dropped to a Category 2 hurricane as it moves northward roughly parallel to the East Coast. However it could get stronger again on Thursday before finally weakening by Friday, the National Hurricane Center in Miami said. It had maximum sustained winds of 100 mph (155 kph) as of Wednesday morning.

The hurricane was about 400 miles (640 kilometers) south-southeast of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, and 560 miles ( 901 kilometers) southwest of Bermuda as of Wednesday morning. Forecasters said Erin was moving north-northwest at 13 mph (21 kph).

Although the weather center was confident Erin would not make direct landfall in the United States, authorities have warned that water conditions along the East Coast remain dangerous. Beachgoers were cautioned against swimming due to life-threatening surf and rip currents.

Officials on a few islands along North Carolina’s Outer Banks issued evacuation orders and warned that some roads could be swamped by waves of 15 feet (4.6 meters).

In the Caribbean, heavy rainfall was forecast for parts of the southeast Bahamas and the Turks and Caicos Islands, the weather center said.

Here is what to know about Hurricane Erin:

Erin poses the biggest threat to the barrier islands of North Carolina’s Outer Banks. Gov. Josh Stein declared a state of emergency Tuesday in advance of the storm, delegating powers to government officials to mobilize workers and equipment along the coast.

The governor said the storm is expected to bring tropical storm force winds, dangerous waves and rip currents to the state. Tropical storm conditions were expected to begin Wednesday.

At least 75 people were rescued from rip currents through Tuesday in Wrightsville Beach, near Wilmington, North Carolina, officials said.

Evacuations were ordered on Hatteras Island and Ocracoke Island on the Outer Banks. The orders come at the height of tourist season on the thin stretch of low-lying barrier islands that juts far into the Atlantic Ocean.

There are concerns that several days of heavy surf, high winds and waves could wash out parts of the main highway running along the barrier islands, the National Weather Service said. Some routes could be impassible for several days.

Warnings about rip currents have been posted from Bermuda and Florida all the way up to the New England coast.

Nantucket is the closest spot in New England to Erin’s anticipated path and was likely to see the strongest winds, gusting about 25 to 35 mph (40 to 55 kph) at peak with waves potentially reaching a height of 10-13 feet (3-4 meters).

Citing treacherous waters, officials prohibited swimming at all beaches in New York City as well as some in Long Island and New Jersey through Thursday.

Bermuda won’t feel the full intensity of the storm until Thursday evening, and the island’s services will remain open in the meantime, acting Minister of National Security Jache Adams said. Storm surge could reach up to 24 feet (7.3 meters) by Thursday, Adams said.

Already this year, there have been at least 27 people killed from rip currents in U.S. waters, according to the National Weather Service. About 100 people drown from rip currents along U.S. beaches each year, according to the United States Lifesaving Association. And more than 80% of beach rescues annually involve rip currents.

Storm surge is the level at which seawater rises above its normal level.

Much like the way a storm’s sustained winds do not include the potential for even stronger gusts, storm surge doesn’t include the wave height above the mean water level.

Surge is also the amount above what the normal tide is at a time, so a 15-foot storm surge at high tide can be far more devastating than the same surge at low tide.

A year ago, Hurricane Ernesto stayed hundreds of miles offshore from the Eastern Seaboard yet still produced high surf and swells that caused coastal damage.

Erin’s strength has fluctuated significantly over the past week.

The most common way to measure a hurricane’s strength is the Saffir-Simpson Scale that assigns a category from 1 to 5 based on a storm’s sustained wind speed at its center, with 5 being the strongest.

Erin reached a dangerous Category 5 status late last week with 160 mph (260 kph) winds before weakening.

Although Erin is the first Atlantic hurricane of the year, there have been four tropical storms this hurricane season already. Tropical Storm Chantal made the first U.S. landfall of the season in early July, and its remnants caused flooding in North Carolina that killed an 83-year-old woman when her car was swept off a rural road.

And, at least 132 people were killed in floodwaters that overwhelmed Texas Hill Country on the Fourth of July.

Just over a week later, flash floods inundated New York City and parts of New Jersey, claiming two lives.

___

Riddle is a corps member for The Associated Press/Report for America Statehouse News Initiative. Report for America is a nonprofit national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms to report on undercovered issues.