The State Department has not held a public press briefing in over three months, even as Washington’s rivals — particularly China and Russia — intensify their communication campaigns to shape opinion and undermine U.S leadership narratives on the world stage.

While the Trump administration has significantly curtailed the number of direct press engagements by officials at the Pentagon and the State Department, Moscow and Beijing are using the public podiums of their foreign ministries as staging grounds for anti-U.S. propaganda campaigns.

The Chinese Foreign Ministry held at least 20 press briefings at its headquarters in Beijing in November, often fielding questions from such Western press outlets as Reuters and Bloomberg on a range of hot topics.

The State Department held a single question-and-answer press conference during the same period.

The Trump administration began 2025 with weekly briefings at the State Department, but they disappeared by the end of the summer.

The shift in communications comes as the U.S. juggles multiple issues like the Russia-Ukraine war, maintaining the ceasefire between Hamas and Israel in Gaza and offering support for Syria’s postwar government.

President Trump’s supporters argue that daily briefings often lack substance and give a stage to what administration officials characterize as anti-Trump mainstream U.S. news outlets.

Those observers say the administration has found a way to engage in effective foreign and defense policy messaging without daily State Department or Pentagon briefings.

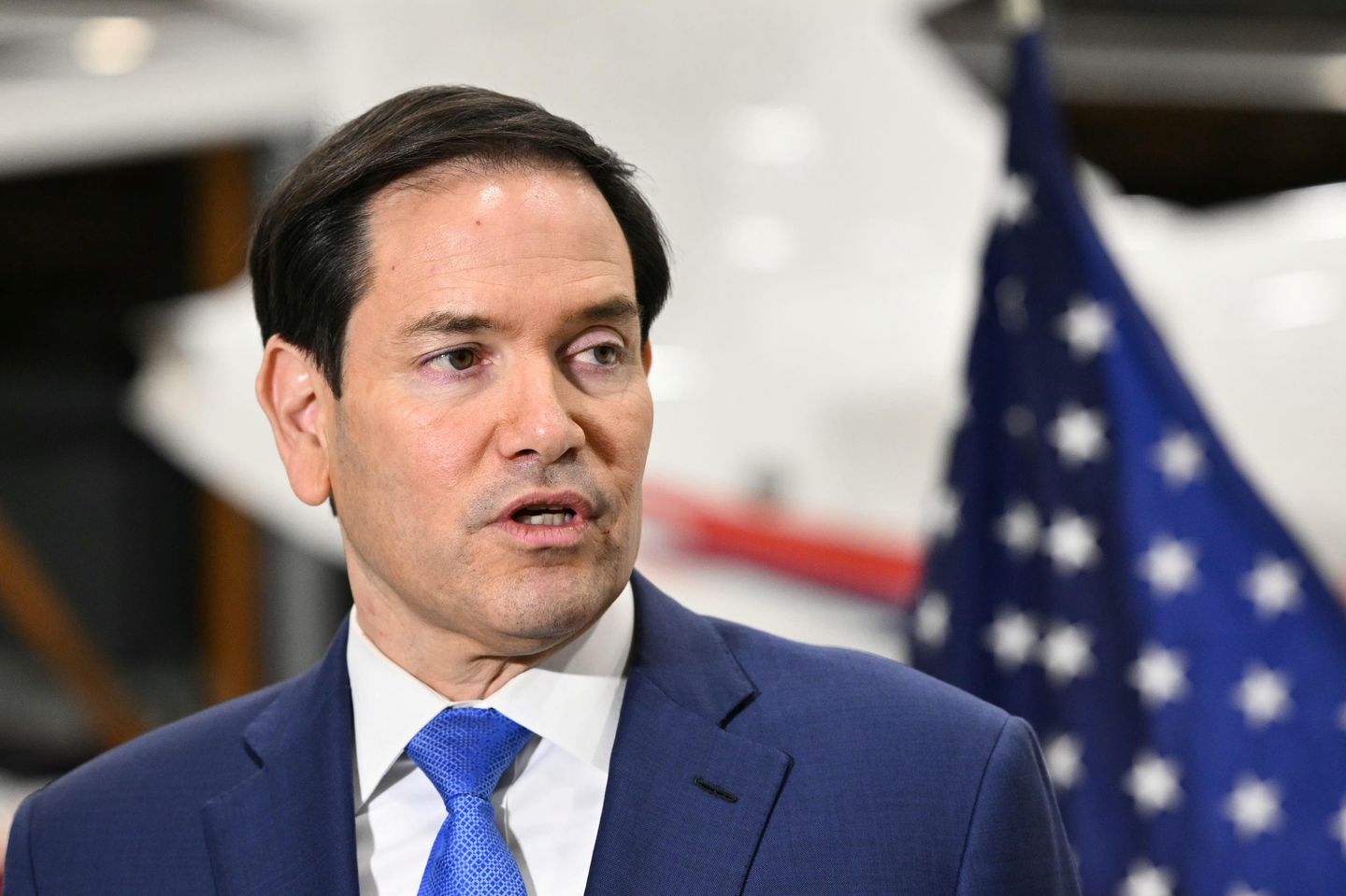

At times, this involves Mr. Trump making policy pronouncements directly via his Truth Social platform. It can also involve speeches by top officials, such as Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth. And some contend Secretary of State Marco Rubio has been an effective communicator when discussing policy directly with media outlets or during engagements with foreign allies and dignitaries.

“The combination of principals, especially Cabinet secretaries or the president, speaking directly with the media, you get a more concise answer, and the rest can be issuing statements,” Christian Whiton, former State Department senior adviser in the second George W. Bush and first Trump administrations, said in an interview. “Cutting back on communication so that the ones that are issued are actually listened to and seen as important.”

Since State Department press briefings dried up at the end of the summer, the department has relied mostly on occasional public statements from Mr. Rubio and other prepared statements.

The department has argued that there’s plenty of public information and that Mr. Trump is “the most transparent president in American history.”

“This administration communicates directly with the American people every single day, through the President’s remarks, press availabilities, and ongoing engagement with reporters,” a department deputy spokesperson said in a statement. “Foreign policy is being discussed openly and frequently by the Secretary, the White House and the President himself.”

However, critics say the administration’s approach has holes in it.

Daily back-and-forth press engagements traditionally give lower-tier administration officials a valuable chance to undergird and amplify top-level policy pronouncements with nuances, deeper details and consistent messaging. Some argue the lack of such engagements risks serious messaging contradictions that can raise alarm bells and sow doubt among U.S. allies and adversaries.

Dan Blumenthal, a senior analyst focused on U.S.-China relations at the American Enterprise Institute, suggests the current administration’s unorthodox approach to policy formulation has only increased that risk.

“The policy process needs to be fixed. Absent that, it is hard to be effective in communicating U.S. policy,” he said in an interview. “Spokesmen need clear guidance on policy that is not internally contradictory.

“Right now, that is not happening. The important thing is clear messaging, which is a function of clear policies.”

Rival ministries stick with briefings

China and Russia have autocratic governments with long traditions of disseminating carefully crafted propaganda to international and domestic outlets. The briefing transcripts are quickly translated into English and posted on the ministries’ websites.

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Mao Ning has used near-daily press briefings in Beijing to defend and amplify her country’s positions on issues from Taiwan to the U.S.-backed Gaza peace plan.

During the Tuesday briefing, a Bloomberg journalist questioned Ms. Ning on what appeared to be worsening relations between Japan and China over comments from Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi, who implied that her defense forces would be activated if Beijing invaded Taiwan.

Ms. Ning seized the opportunity to slam Japan, a leading democracy and key U.S. security ally on China’s periphery.

“Essentially, the Japanese side has been deliberately evading China’s call for it to retract the erroneous remarks and hoping that somehow the issue would resolve itself. We could not but question whether the Japanese side does have the sincerity and whether it will take action to do serious soul-searching and correct its wrongdoing,” Ms. Ning said.

Russian briefings are far more scripted, with the Russian Foreign Ministry not allowing direct questions from the press. But the ministry still holds a steady flow of briefings to project the Kremlin’s view on a stage closely watched by media outlets from around the world, including from countries teetering between siding with the U.S. or Russia.

Russian Foreign Ministry spokesperson Maria Zakharova regularly uses the briefing podium to attack Europe’s support for Ukraine and to counter Washington and Kyiv’s messaging surrounding peace negotiations.

Several former State Department officials told The Washington Times that the Trump administration should be doing the same.

One of the former officials, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said U.S. officials need aggressive leadership willing to enforce messaging discipline with thought-out frameworks, with or without regular press briefings.

A direct line to the White House

Regular weekly or daily press briefings have been a Washington tradition since the 1950s.

Cutting back on briefings at the State Department comes as the White House works to consolidate bureaucracy across executive agencies, creating a direct line from the president to the person responsible for publicly communicating U.S. policy.

“For many years, there has been a trend that concentrates more domestic and international foreign policy messaging around the White House. Under President Trump, this dynamic is on steroids, especially when he hosts world leaders in the Oval Office,” said P.J. Crowley, a retired Air Force colonel and former assistant secretary of state for public affairs.

“He can establish policy, modify it and reverse it within a single media opportunity. Add to this the fact that Marco Rubio is sitting next to him as both the secretary of state and national security adviser,” Mr. Crowley said.

He added that it’s easier for the State Department “to let the White House take the lead” than keep up with the frequent policy pivots of the Trump administration.