The U.S. decision to help South Korea build a nuclear-powered submarine could spell the end of the push for denuclearization in Northeast Asia and threatens to upset the global nonproliferation regime, some experts say.

Speaking at this week’s Washington Brief, a monthly online forum hosted by The Washington Times Foundation, retired Marine Lt. Gen. Wallace “Chip” Gregson argued that providing South Korea with nuclear-powered capabilities is not a simple prospect.

“If South Korea decides that they want to expend national resources to achieve a nuclear submarine capability, they will be able to do it, and we should help with it to make sure that proper precautions, security and everything are taken,” Mr. Gregson said. “But this also creates an alliance problem for us, because then which of our other allies want nuclear submarines? Japan would be about a day behind South Korea in developing the technology for a nuclear submarine if South Korea wants to have a nuclear submarine.”

During his visit to the region last month, President Trump announced the U.S would help South Korea develop and build nuclear-powered submarines. The U.S. greenlight makes South Korea a blue water navy, meaning its ships can travel far beyond its nation’s waters. Only the U.S., China, Russia, India and the U.K. field nuclear-powered subs.

Australia is in line to acquire nuclear-powered subs through the AUKUS agreement with the U.S. and the U.K. but isn’t expected to receive them for several years.

The subs, which will be powered by uranium enriched within South Korea, will let Seoul dive deep into the Pacific Ocean to track Chinese and North Korean vessels and support U.S. forces in the surrounding territory.

The subs, which will be powered by uranium enriched within South Korea, will let Seoul dive deep into the Pacific Ocean to track Chinese and North Korean vessels and support U.S. forces in the surrounding territory.

Powered by South Korean-enriched uranium, the submarines could chase after trespassing Chinese or North Korean vessels.

The nuclear-powered subs might change the balance of power in Northeast Asia. During the Washington Brief, Mr. Gregson pondered what the South Koreans were getting out of their new nuclear capability.

“South Korea’s about to face a shock when they learn what’s necessary to have a nuclear arsenal, and how much it costs,” he said. “And the question is, what gain do you get? What does nuclear propulsion on a submarine do for South Korea, given their security situation with North Korea, that a conventional submarine with the same weapons does for South Korea? All this remains to be seen.”

South Korea’s upcoming nuclear capabilities signal a dramatic shift in Seoul’s relationship with Washington. Since taking office, Mr. Trump has insisted that U.S. allies in Asia and Europe should take on more responsibility for their defense and has called on South Korea to contribute more of its gross domestic product to military spending.

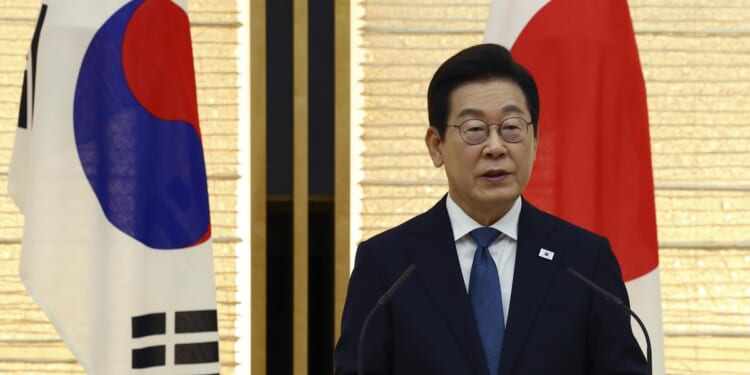

South Korean President Lee Jae-myung asked lawmakers this week to approve an 8.2% increase in defense spending for 2026, which could assist in Seoul’s new nuclear sub project.

South Korea has pushed for more military autonomy for years, especially as a way to stand up to North Korea, which has rapidly developed its ballistic missile and nuclear weapons programs over the past decade.

A South Korean nuclear sub could also mark the end of an era of denuclearization in Northeast Asia. For years, the U.S. and other Western powers have urged North Korea to come to the table to discuss disarming its nuclear arsenal, but Pyongyang’s allies, Russia and China, have essentially ruled out such talks.

During the Washington Brief, Mr. Gregson and Alexandre Mansourov, professor of security studies at Georgetown University, said giving South Korea the ability to build nuclear-powered subs could get the ball rolling on further nuclear capabilities and introduce complicated defense questions for Seoul.

“South Korea achieving a nuclear weapons status would be a real blow to nonproliferation. It would also be a real blow to the alliance. We have extended deterrence guarantees for South Korea and Japan and the Philippines and our other allies,” Mr. Gregson said. “South Korea needs to recognize that there is no military utility to having nuclear weapons in South Korea. There are a lot of downsides. You have to build an infrastructure to support them, you have to build an infrastructure to protect them.”

Still, the U.S. has signaled that it is interested in continuing its dialogue with North Korea. During his Asia trip, Mr. Trump indicated that he would be open to speaking with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un. However, the meeting never happened, with Mr. Kim dispatching his foreign minister to meet with diplomats in Russia.

South Korea’s National Intelligence Service reported Tuesday that Mr. Kim may seek to restart dialogue with the U.S. next year if conditions are favorable. The agency predicted that such a summit may take place in March following U.S.-South Korean joint military exercises.