The White House says President Trump is “determined” to maintain at least a 10% tariff on all imports, meaning all nations should expect a baseline tax on their goods even if they negotiate trade pacts with the U.S.

Dozens of trading partners are scrambling to negotiate down sky-high levies that Mr. Trump imposed, then paused, in early April. It’s a fluid process, but this much should be clear: Mr. Trump will only go so low.

“The president is determined to continue with that 10% baseline tariff. I just spoke to him about it earlier,” White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt said Friday.

Mr. Trump imposed a blanket tariff of 10% on all imports as part of a “Liberation Day” plan at the heart of the White House trade agenda. It was a major change in U.S. trade policy, yet one overshadowed by his threat to slap much higher “reciprocal” tariffs on major trading partners, including 46% on Vietnam and 26% on India.

“A blanket 10% tariff is a major upheaval. In 2024, the average tariff in the United States was about 2.5%, so this is now four times larger,” said Clark Packard, a research fellow on trade at the libertarian Cato Institute.

Tariffs are a tax or duty paid by importers on the goods they bring in from foreign markets.

Foreign countries don’t pay the tariffs directly to the U.S. Treasury. In many cases, U.S. companies will pay the levies, and they might pass on at least some of the cost to consumers through higher prices.

The impact of the blanket 10% tariff on goods isn’t clear just yet – many retailers tried to frontload shipments this year to get ahead of the levies.

But it’s here to stay, and some trade experts say it is a big deal – and a big risk — since the impact will be compounded by even higher tariffs on imported inputs like steel and aluminum.

“America now has the developed world’s highest tariffs. The only countries with similar burdens tend to be very poor — in part because of those high trade barriers,” said Ryan Young, a senior economist at the Competitive Enterprise Institute.

Mr. Trump says tariffs are a great way to force companies to return to America or keep their operations in the U.S., employ American workers and create revenue to fund domestic programs.

Tariffs were a key source of revenue for the U.S. before the federal income tax was imposed in the early 20th century, and Mr. Trump said the U.S. would be taking in lots of money again.

Britain was an early test case of how dedicated Mr. Trump is to imposing a base level of tariffs on friends and foes alike.

It still faces a blanket 10% levy on its goods despite inking a trade deal in principle Thursday that lowers sector-specific tariffs on steel, aluminum and a fixed number of British car exports.

“The president is committed to the 10% baseline tariff, not just for the United Kingdom but also his trade negotiations with all other countries as well,” Ms. Leavitt said.

Mr. Trump suggested the U.K. got a good deal with a 10% tariff.

“That’s a low number,” he said. “They made a good deal. Some will be much higher because they have massive trade surpluses.”

Mr. Trump is using trade deficits — situations in which countries sell plenty of products to American consumers but don’t buy nearly as much from U.S. producers — to drive his trade policy.

If the U.S. has a big trade deficit with a specific country, that nation faces a higher reciprocal tariff under Mr. Trump’s plan.

Experts said some nations will be eager to negotiate even if they face at least a 10% tariff from the U.S. side.

“It depends. Some countries faced tariffs well above 10% when President Trump announced the ‘Liberation Day’ tariffs. Those countries may find it advantageous to negotiate,” Mr. Packard said.

Others said it might harm negotiations.

“The fact that the U.K. agreement is concluding with higher U.S. tariffs than it began with is not helping America’s negotiating stance with Europe and other allies,” Mr. Young said. “They don’t see as much to gain. Countries are pivoting away from the U.S. and towards other alliances, to China’s benefit.”

As it stands, the U.S. and China are locked in a trade war with tariffs exceeding 100% on either side.

Mr. Trump on Friday said China could face an 80% tariff on its goods. It is a drastic reduction from the 145% tariff that he is currently imposing on Chinese goods, but sets an aggressive guidepost for weekend talks.

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent and U.S. Trade Representative Jamieson Greer will meet with Chinese counterparts in Geneva to try and de-escalate the trade war between the world’s largest economies.

“80% Tariff on China seems right! Up to Scott B,” Mr. Trump wrote.

Whatever the number, Ms. Leavitt said the U.S. will not lower tariffs on its own.

“He’s not going to unilaterally bring down tariffs on China. We need to see concessions from them as well,” she said.

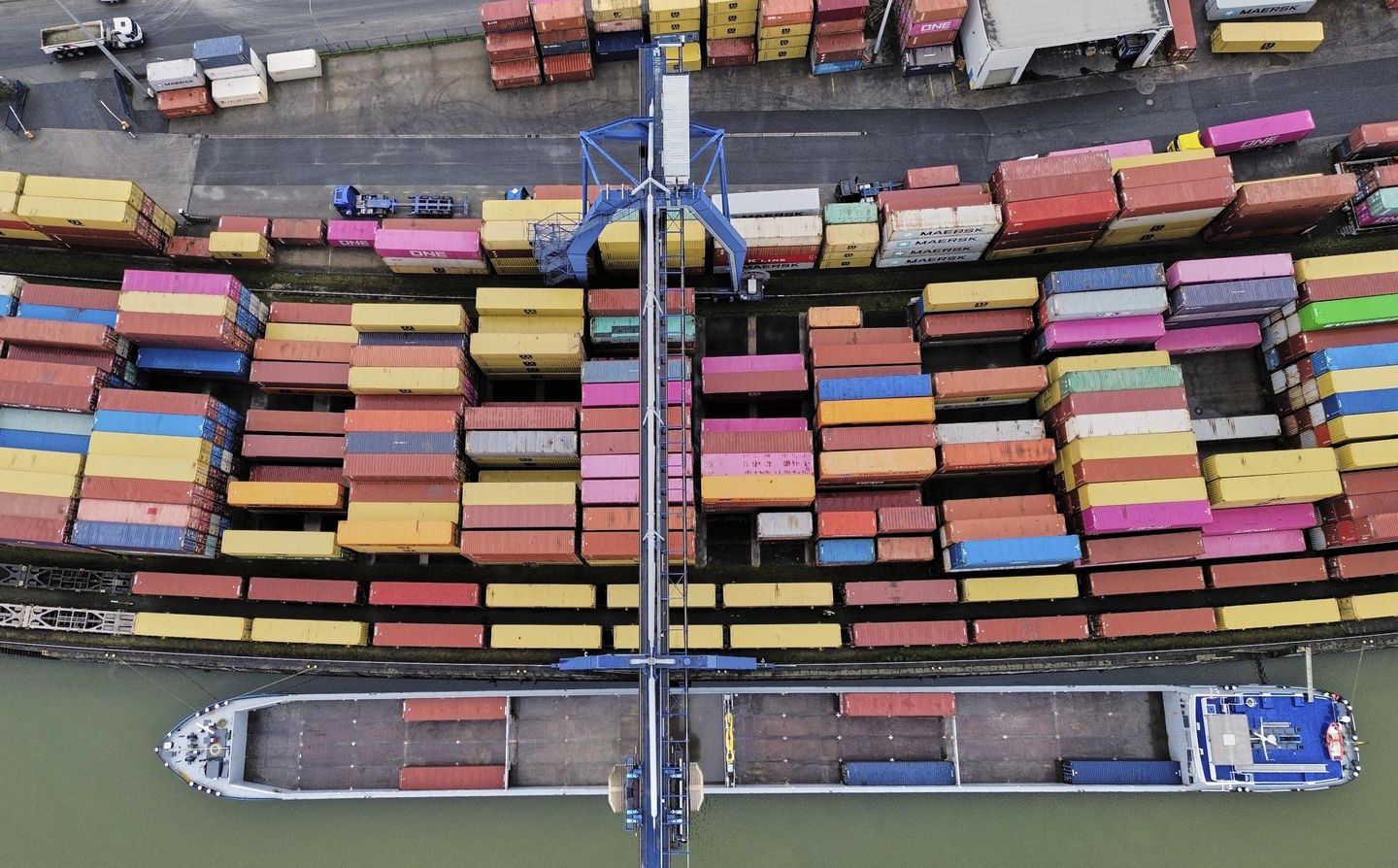

In the meantime, shipping across the Pacific Ocean is starting to slow down as Washington and Beijing refuse to budge first.

Factory output in China is slowing down, while U.S. consumers could see fewer products or higher prices.

In his online posts, Mr. Trump said China’s market is too restrictive.

“CHINA SHOULD OPEN UP ITS MARKET TO USA — WOULD BE SO GOOD FOR THEM!!! CLOSED MARKETS DON’T WORK ANYMORE!!!” Mr. Trump wrote.

Ahead of talks, Ms. Leavitt said: “China needs the United States of America” and defined success as “a good deal for the American people and the American worker.”

Mr. Trump also said that “many trade deals are in the hopper,” which appeared to enthuse Wall Street.

Stocks were up after the opening bell Friday but sank later in the day. The Dow Jones Industrial Average fell over 100 points, or .29%, while the S&P 500 slid .07% and the Nasdaq broke about even.

The U.S. exported $143.5 billion in goods to China in 2024 while importing $438.9 billion from the Chinese, for a trade deficit of $295.4 billion, according to the U.S. Trade Representative.

Negotiating with China may be the toughest task for Mr. Trump’s trade team, even as it sees progress in negotiating down trade barriers in other countries.

The U.S. and U.K. announced their trade agreement in principle on Thursday.

American producers, particularly farmers, will get more access to the British market, and U.K. companies will be able to supply critical parts to American companies like Boeing.

Many saw the deal as a win for both Mr. Trump and U.K. Prime Minister Keir Starmer.

Not everyone is happy, however.

The American Automotive Policy Council, which represents Ford Motor Company, General Motors Company and Stellantis, said the U.K. deal seemed to prioritize British vehicles ahead of cars that are manufactured with North American partners under the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement.

“Under this deal, it will now be cheaper to import a U.K. vehicle with very little U.S. content than a USMCA-compliant vehicle from Mexico or Canada that is half American parts,” said Matt Blunt, president of the council and a former Republican governor of Missouri. “This hurts American automakers, suppliers, and auto workers. We hope this preferential access for U.K. vehicles over North American ones does not set a precedent for future negotiations with Asian and European competitors.”

Ms. Leavitt said the 10% tariff on British automobiles only applies to the first 100,000 vehicles out of Britain before going back up to 25%.

“By the way, if they produce vehicles right here in the United States of America, they will face no tariff at all,” she said.