BELEM, Brazil — Several nations and environmental groups on Friday slammed proposals in the final stages of this year’s U.N. climate talks for failing to explicitly mention the cause of global warming – the burning of fuels such as oil, gas and coal – with one negotiator warning the talks are on “the verge of collapse.”

Juan Carlos Monterrey Gomez, a top negotiator for Panama, said the decades-long United Nations process risks “becoming a clown show” for the omission. His nation was among 36 to object to a proposal from conference president André Corrêa do Lago of host Brazil because it doesn’t provide an explicit guide map for the world to transition away from fossil fuels, nor strengthening climate-fighting plans submitted earlier this year.

Do Lago countered by telling negotiators he thought they were “very close” to doing what they set out to do when they started meeting a week ago.

The Brazilian proposals came on what was supposed to be the last day of the talks, and on the heels of a fire on Thursday that briefly spread through pavilions of the conference known as COP30 on the edge of the Amazon. No one was seriously hurt but the fire meant a largely lost day and increased the likelihood the talks would sprawl into the weekend, as they frequently do.

The European Union said flatly that it wouldn’t accept the text. EU climate commissioner Wopke Hoekstra reminded negotiators that countries had gathered at the edge of the Amazon to bring down emissions and transition away from fossil fuels.

“Look at the text. Look at it. None of it is in there. No science. No global stocktake. No transitioning away. But instead, weakness,” Hoekstra said in a closed-door meeting of negotiators, according to a transcript provided by the EU. “Under no circumstances are we going to accept this. And nothing that is even remotely close, and I say it with pain in my heart, nothing that is remotely close to what is now on the table.”

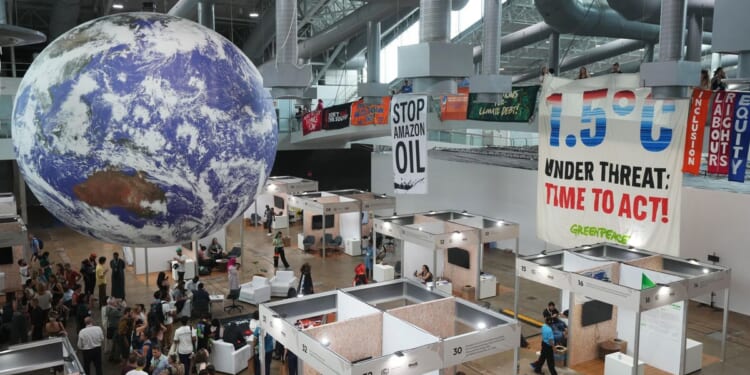

PHOTOS: Nations and environmental groups slam proposals at UN climate talks, calling them too weak

“After 10 years, this process is still failing,” Maina Vakafua Talia, minister of environment for the small Pacific island nation of Tuvalu, said in a speech earlier in the day. “The Pacific came to COP30 demanding a survival road map away from fossil fuels. Yet the current draft texts that came out (do) not even name the main threat for our very survival and existence.”

A key text among host Brazil’s proposals deals with four difficult issues. They include financial aid for vulnerable countries hit hardest by climate change and getting countries to toughen up their national plans to reduce Earth-warming emissions.

Then there’s the dispute over creating a detailed road map for the world to phase out the fossil fuels that are largely driving Earth’s increasing extreme weather. Any such plan would expand on a single sentence – to “transition away” from fossil fuels – agreed upon two years ago at the climate talks in Dubai. But no timetable or process was spelled out and powerful oil-producing nations like Saudi Arabia and Russia oppose it.

More than 80 nations have called for stronger direction and Brazil President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva also pushed for it earlier this month.

Former U.S. Vice President Al Gore urged nations to stand firm in opposition and hailed Lula’s involvement.

“Saudi Arabia and Donald Trump and Russia under Vladimir Putin have bullied countries to support an absurd proposal,” Gore said in an interview with The Associated Press. He said the latest document “even deletes the proposal to phase out the ridiculous and self-destructive subsidies for fossil fuels. This is an OPEC text,” he said, for the organization that represents oil-producing countries.

On phasing out fossil fuels, the proposal “acknowledges that the global transition towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development is irreversible and the trend of the future.”

The text “also acknowledges that the Paris Agreement is working and resolves to go further and faster,” referring to the 2015 climate talks that established the goal to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit), compared to the mid-1800s. A key issue is that the 119 national emissions curbing plans submitted this year don’t come close to limiting warming to 1.5 degrees.

Though the text didn’t address a fossil fuel transition road map, it could eventually end in a vaguely worded section about a plan for the next couple years in a separate road map.

The 36 nations who thought the text didn’t go far enough included wealthy ones such as the United Kingdom, France and Germany along with smaller climate vulnerable islands Palau, Marshall Islands and Vanuatu. They said the proposal doesn’t meet “the minimum conditions required for a credible COP outcome.”

Colombian Environment Minister Irene Vélez Torres said the presidency’s proposal is unacceptable to “those of us who are committed to life on this planet, to climate justice.”

Agreements at these talks are officially reached when no nation objects and typically require many rounds of negotiations. In practice, the proceedings can end with agreements adopted and the presidency adjourning the meeting after noting any objections.

Instead of the usual small group meetings, the Brazilian presidency convened a meeting of nations’ top officials behind closed doors for much of Friday. It’s designed to lessen any nation feeling left out of backroom deals, but it doesn’t let the public see countries’ objections.

“Far from a promised ‘COP of Truth’ this summit has become a master class in exclusion,” veteran climate activist Harjeet Singh said.

But another longtime COP observer, Alden Meyer of the European think tank E3G, said getting ministers in the same room was a necessary step.

___

Associated Press journalist Teresa de Miguel contributed.

___

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. The AP is solely responsible for all content. Find the AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

___

This story was produced as part of the 2025 Climate Change Media Partnership, a journalism fellowship organized by Internews’ Earth Journalism Network and the Stanley Center for Peace and Security.