SEOUL, South Korea — Addressing U.S. President Trump Wednesday during his state visit to the U.K., King Charles III said, “Our AUKUS submarine partnership with Australia sets the benchmark for innovative and vital collaboration.”

That remark was reported by Australian media as a “kaboom” moment.

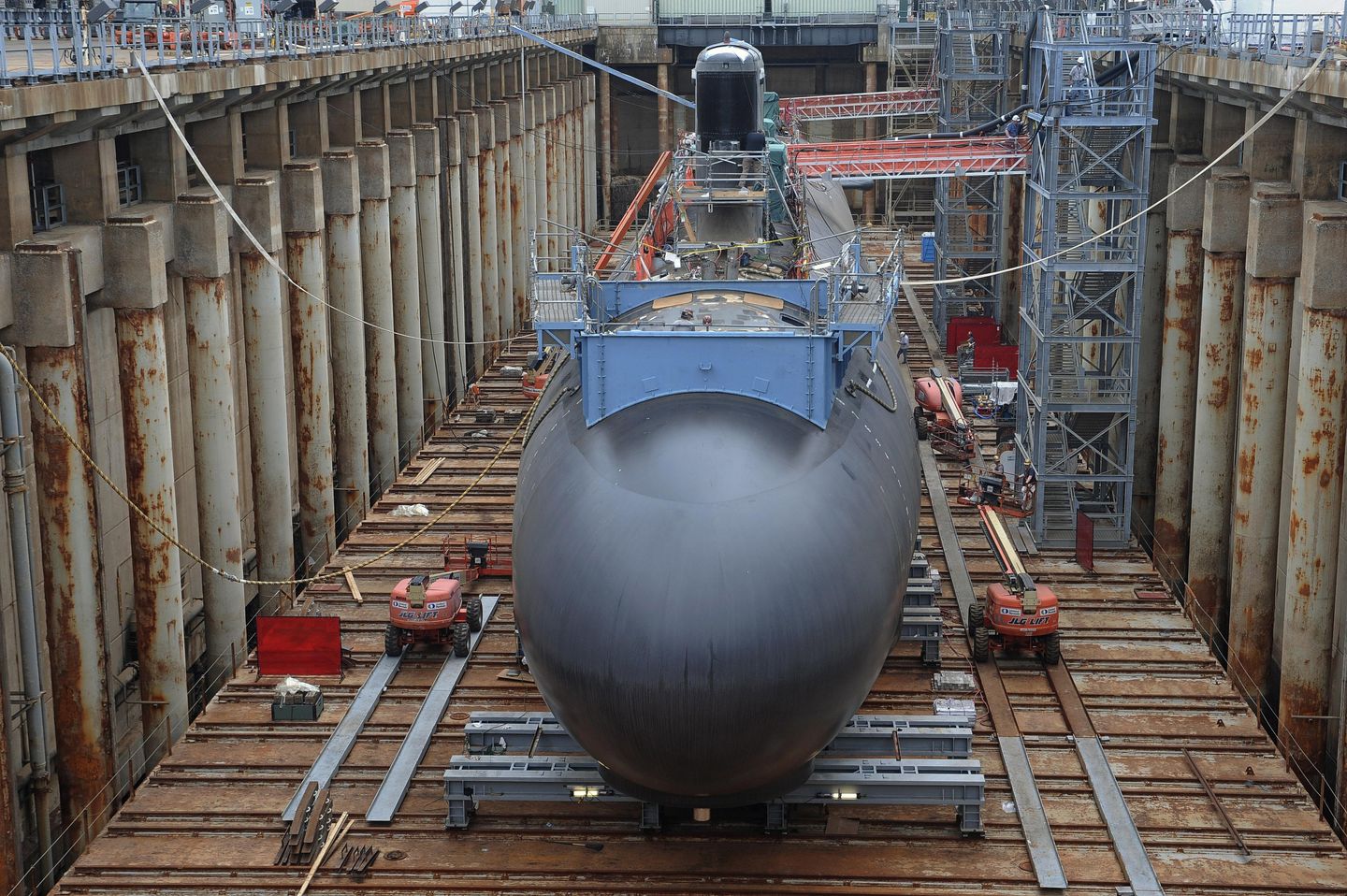

Under AUKUS — shorthand for the trilateral security agreement between Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States — the U.K. and the U.S. agreed to supply Australia with nuclear attack submarines.

The king’s reference is seen as a not-too-subtle reminder to Mr. Trump, who has been noncommittal about delivering on a pledge made by the Biden administration, that the British aren’t simply ceding the defense of their allies and interests in the Indo-Pacific to the Americans.

Disagreements between the Europeans and the U.S. over Ukraine’s defense are widely known. But a quieter controversy is brewing between the U.S. and Western allies over a sense that the Americans are asking the Europeans to take a backseat when it comes to leadership and defense in the Pacific.

Some Washington figures have argued that NATO nations should aim their limited capabilities at Russia, puncturing European egos accustomed to global influence. But growing global skepticism about Mr. Trump’s “America First” policies has some Indo-Pacific capitals linking hands with Europe on defense partnerships and arms deals.

“The United States is historically Europe’s closest ally, and the Indo-Pacific is becoming increasingly important to European strategy,” the German Marshall Fund wrote on Sept. 11. “However … differing views and approaches within the U.S. administration, and uncertainty about Washington’s approach to China, make it particularly challenging for Europe to carve out room to maneuver as a security actor.”

From CRINK to CRNK?

Chinese President Xi Jinping, North Korean leader Kim Jong-un and Russian President Vladimir Putin made up the front rank of leaders at Beijing’s military parade to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II in the Pacific on Sept. 3.

Conspicuously absent from prestige positioning was visiting Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian.

Iran is commonly lumped into the authoritarian bloc of China, Russia, Iran and North Korea — sometimes referred to as CRINK, but also known as “The Axis of Upheaval” or “The Axis of Authoritarianism.”

But Iran’s military humiliation at the hands of U.S. and Israeli forces has shaken up the status quo.

“They got the hell knocked out of them recently,” said Grant Newsham, a former U.S. Marine officer and diplomat with wide experience in the Indo-Pacific.

Tehran’s proxies Hamas and Hezbollah have been degraded, and its own air defenses were shattered, leaving nuclear sites at the mercy of Israeli and U.S. bombers, which suffered no losses in their operations.

While Iran has been de-fanged for now, nuclear-armed China, North Korea and Russia represent a formidable triad.

All are Indo-Pacific powers with global presence.

Though Russia is fighting a bloody war on its European frontier, it maintains a significant military presence in the Far East.

And Beijing deploys a world-ranging naval fleet that has conducted drills with Russia as distant as the Indian Ocean.

Pyongyang has fought in Russia’s war against Ukraine and is receiving military — including maritime — technologies from a grateful Moscow.

Democracies struggle to respond

America, with both Atlantic and Pacific seaboards, maintains a massive presence in the Indo-Pacific and has allies in Australia, Japan, the Philippines and South Korea, while unofficially underwriting Taiwan’s defense.

Euro-Atlantic NATO members have small but active presences in the Indo-Pacific.

The U.S.-led U.N. Command — the free-world states that defended South Korea during the 1950-53 Korean War — includes representatives from Europe, including France and the U.K.

Germany joined in 2024, a European officer said, “To get a bootprint in Indo-Pacific.”

However, bar the U.S., no UNC states have mutual defense treaties with Korea, nor on-ground units.

The Proliferation Security Initiative, or PSI, has seen European warships patrolling regional waters to oversee sanctions on North Korea.

Drills are another eastward call. Europe is increasingly sending forces to join regional exercises, such as Australia’s Jet Black and Talisman Saber.

Mid-sized powers France, Italy and the U.K. have deployed carrier strike groups in recent years. These voyages are not just operational: Flight deck cocktail parties generate diplomatic/commercial PR.

“Efforts at defense diplomacy — sending CSGs to demonstrate capabilities, but also to boost potential weapons sales — show that Brits and Europeans have skin in the game,” said Alex Neill, a regional security expert at Pacific Forum. “But maybe the U.S. thinks it is a complicating effort and they would be better using those assets to defend closer shores.”

It is questionable whether European militaries deter Beijing’s or Pyongyang’s huge forces.

“I doubt Europeans have much to offer when it comes to Asia-Pacific since their militaries are just too small,” said Mr. Newsham. “They’re hard pressed to take care of their own area, much less farther afield.”

Potentially, European CSGs could “backfill” U.S. CSGs departing Euro-Atlantic for Indo-Pacific. Some might fight, as the Royal Navy did alongside U.S. forces in World War II and the Korean War.

However, U.S. Department of Defense Undersecretary Eldridge Colby has deprioritized the Atlantic for the Pacific.

He sought to delay shipments of weapons needed by Ukraine — a decision overturned by Mr. Trump.

Europe’s limitations

In May, according to reports that were not refuted, Mr. Colby told British officials that their CSG was not wanted in the Indo-Pacific.

Brits were apparently stunned: The eight-month, ongoing tour by the Royal Navy’s flagship is a high-prestige global mission for London.

Regionally, the U.K. CSG has cooperated effectively with local forces from India to Japan — and with the U.S. Navy. A British frigate, together with a U.S. destroyer, transited the Taiwan Strait on Sept. 12, angering Beijing.

But the regional deployment exposed limitations.

“The Royal Navy can’t even put up a full CSG, it needs assistance from partner nations,” Mr. Neill said, referencing shortfalls in F-35s and surface escorts. “And you read about assets breaking down along the way.”

London may have caved to U.S. pressure.

In July, one of the lead drafters of the U.K.’s Strategic Defense Review, told Parliament that “the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command … does not see much value in U.K. forces being based in the region,” leading to a British refocus on “the Atlantic bastion.”

Paris has stronger claims to regional presence — and may be more resistant to Washington.

“The Brits and the EU constantly bang the drum about maintaining global order and freedom of navigation in Indo-Pacific,” said Mr. Neill. “France argues that they are a resident power in Indo-Pacific and has 2 million citizens living in the Indian Ocean and the Pacific.”

2021’s AUKUS was placed under review by Mr. Colby in June, under the logic that the U.S. Navy needs all the submarines U.S. yards can build.

If Washington quashes AUKUS, it would humiliate London and Canberra. Both have staked political and financial capital on it.

But a source familiar with regional security told this newspaper that “Bridge (Colby’s nickname) is losing steam.”

American and Australian media report that U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has assured Australian officials that AUKUS will proceed.

Even so, “America First’ is testing nerves among allies — and ex-U.S. synergies are developing.

“Trump, perhaps unwittingly, has acted as a catalyst for greater European and Asian innovation by liberal democratic states in foreign and security policy,” said John Nilsson-Wright, an Asia expert at Cambridge University.

New partnerships

In 2023, Japan and the U.K. signed a legal-military deal enabling the swift, seamless deployment of troops and arms between the two nations.

Japan is working, not with a U.S. defense contractor, but with British and Italian partners, to develop a 6th-generation stealth fighter.

Japan and South Korea are benefiting from their alliances with the U.S., which required them to use NATO-standard gear. This means their arms firms can increasingly compete with the U.S. MIC.

While neither Seoul nor Tokyo has armed Kyiv, Korean arms firms have benefited massively from the Ukraine War, selling arms worth tens of billions of dollars to NATO nations including Estonia, Norway, Poland, Romania and Turkey.

Mr. Nilsson-Wright argues that multilateral defense linkages must be maintained or upgraded.

“A global commitment is required from middle-ranking powers,” he said, in order to “…compensate for the long-term decline in U.S. influence.”