Black Californians waiting for the state to start cutting seven-figure checks to the descendants of American slaves may not want to hold their breath.

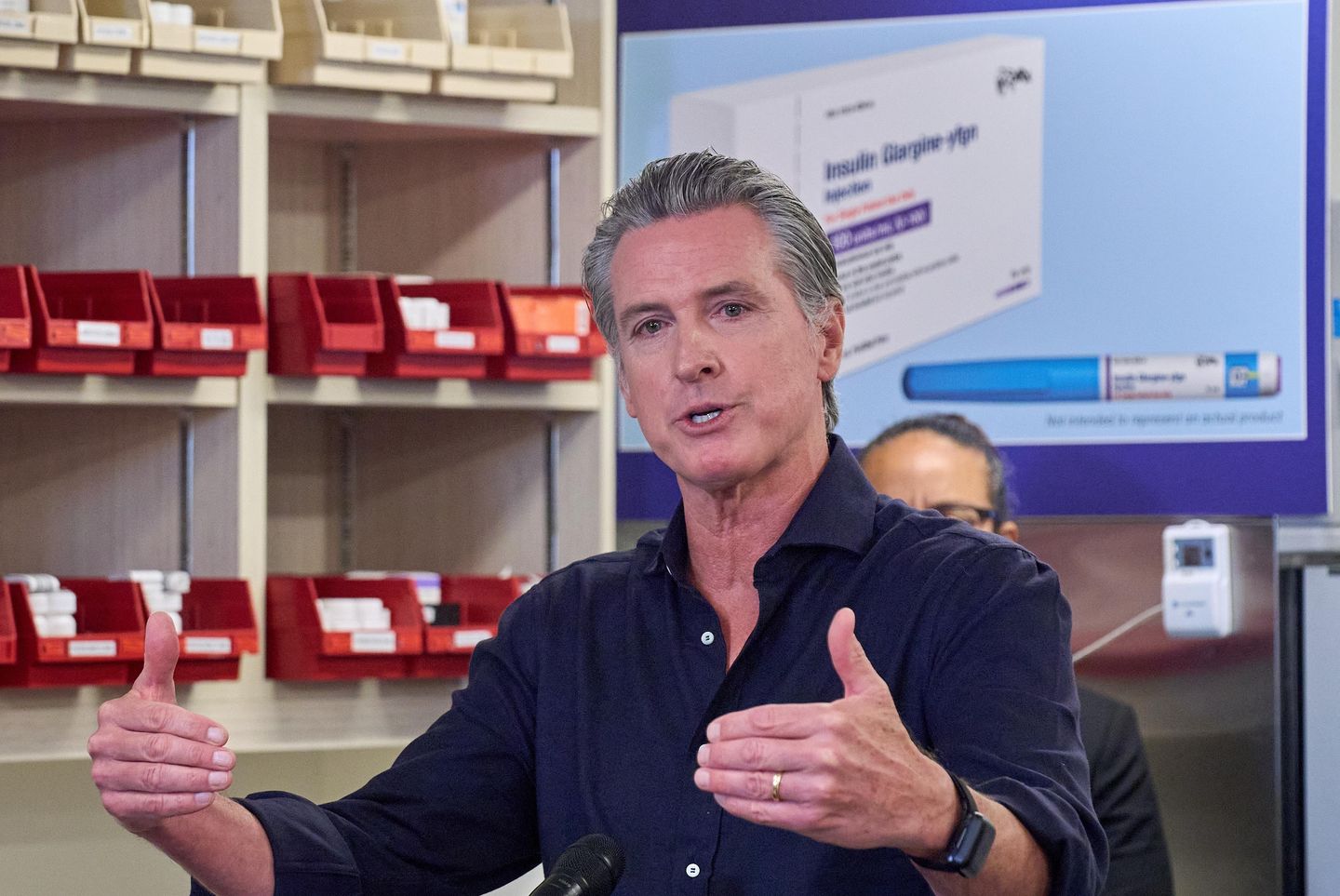

Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom vetoed five of the 10 bills backed by the Legislative Black Caucus in its Road to Repair package, the latest bid to implement the vision of the California Reparations Task Force more than two years after it completed its work.

Mr. Newsom signed Assembly Bill 518, which establishes a Bureau for Descendants of American Slavery, and Senate Bill 437, which authorizes $6 million for California State University to research methods of determining slavery ancestry.

But he drew the line on legislation providing benefits to individuals.

He vetoed bills allowing colleges to give priority admissions to descendants of slaves; setting aside loans for slavery descendants buying their first homes; and requiring the state to investigate claims of property seized through racially motivated eminent domain and compensate any victims.

Mr. Newsom called the admissions bill “unnecessary,” saying that universities may now offer such preferences as permitted by federal law, and cited legal risks and limited resources as factors in his decision to veto the other measures.

“My administration shares the commitment to dismantle systemic racism, including by addressing the wealth gap,” he said in his veto message for AB 62, the eminent-domain bill.

The caucus opted to look on the bright side, thanking Mr. Newsom for signing the five bills and stressing that California has become the first to approve a bureau “tasked with ensuring equitable access for a historically marginalized community.”

“While not all of our bills were signed into law, a lot of good work has been done this year,” said Democratic state Sen. Akilah Weber Pierson, the caucus chair. “Progress takes time and the CLBC will continue to fight for Black Californians.”

Less sanguine was Assemblymember Isaac Bryan, sponsor of the university admissions bill, who called the governor’s veto “more than disappointing.”

“While the Trump administration threatens our institutions of higher learning and attacks the foundations of diversity and inclusivity, now is not the time to shy away from the fight to protect students who have descended from legacies of harm and exclusion,” he told The Associated Press.

Also frustrated was the Coalition for a Just and Equitable California, which dismissed the newly authorized agency as “yet another government bureaucracy” that “provides no payments, restitution, or wealth restoration.”

“Let’s be clear — SB 518 is not real Reparations, nor is it a step closer to real Reparations,” said coalition spokesperson Chris Lodgson in a statement. “It’s a bureaucratic shell that delays Reparations, expands beyond the lineage it claims to serve, and diverts precious time and resources away from the real work of repair.”

He added: “Reparations delayed, Reparations diverted, is Reparations denied.”

In June 2023, California’s first-in-the-nation reparations task force issued a 1,100-page report that envisioned payouts of up to $1.2 million for slavery descendants based on factors such as “health discrimination,” “mass incarceration and overpolicing,” and the “life expectancy gap.”

Mr. Newsom applauded the task force’s work, but ruled out the possibility of cash payments.

He signed legislation in 2024 issuing a formal apology for the state’s role in perpetuating slavery and discrimination.

Andrew Quinio, an attorney with the conservative Pacific Legal Foundation in Sacramento who tracks reparations, said that the caucus lawmakers “fell very short of their goal.”

“The tangible things that they were seeking from the state of California did not come to fruition because Newsom vetoed those bills,” Mr. Quinio told The Washington Times. “Even with the passage of 518 and the new Bureau for Descendants of American Slavery, ultimately they’re just getting another government bureaucracy.”

He said the caucus did have more success than in the previous legislative session as more bills made it out of committee and onto the governor’s desk.

Even so, the legal landscape and public opinion continue to loom as obstacles to the goal of financial payouts.

“I think the dream of having cash payments as reparations is not going to happen for a while, and maybe not at all,” Mr. Quinio said. “Even San Francisco toyed with the idea of doing cash reparations, and they very quickly got rid of that idea. It goes back to what is legal, what is constitutional.”

While California entered the union in 1850 as a free state, meaning it did not sanction slavery, records show that the state enforced the Fugitive Slave Act and that owners brought in slaves from other states to work during the Gold Rush.