ROSEAU, Dominica — Traveling up the winding mountain roads of the Caribbean nation of Dominica, a little-known tropical paradise in the Lesser Antilles, it’s easy to see how this tiny country came to be known as “Nature Island.” Blessed with lush rainforests, an abundance of waterfalls and pristine black sand beaches, this volcanic island of 72,000 inhabitants is also home to the Boiling Lake, the world’s second-largest natural hot spring.

But with parts of its infrastructure still recovering from a devastating 2017 hurricane, a shortage of modern hotels and an airport lacking direct flights from major hubs, Dominica often flies under the radar for Americans. The island, like other outposts in the Caribbean, is attracting plenty of attention these days from another superpower — the signs of Chinese interests and investments are everywhere in Dominica.

Despite its natural beauty, Dominica is relatively underdeveloped as a tourist destination — it attracts around 339,000 visitors annually, a fraction of the 10 million who set foot each year in the Dominican Republic, for example.

But Dominica is undergoing a transformation reflective of a broader regional trend: The Caribbean is no longer just “America’s backyard” — it is increasingly a key cog in the machine of China’s global expansion machine.

Central to this transformation is the ongoing construction of Dominica’s new international airport, a flagship project financed and built by Chinese companies.

Perched high on a jungle ridge near the village of Wesley, bulldozers and Chinese-made excavators tear at the hillsides to carve out what will become the island’s first international airport. Scheduled for completion in 2026, the project is emblematic of Beijing’s regional strategy: all over the Caribbean, large-scale infrastructure initiatives are being carried out by Chinese firms and workers, bringing tantalizing promises of long-term economic development.

According to Chinese state media, once finished, the Dominica facility will host flights from Europe and North America and bring a half-million passengers per year to the island. Mandarin signage, Chinese construction crews, and Chinese-branded equipment are a ubiquitous sight on many Caribbean islands, pointing to the PRC’s growing influence in the region.

Local perceptions, however, are mixed, with many Dominicans expressing concerns that Chinese-backed projects bring few jobs to locals, as labor is often imported directly from China.

“The only problem I see is that they don’t hire Dominicans, they only ever bring their own people to work. People here need jobs, you know”, said Lee, the owner of a popular beachside bar and restaurant in Calibishie, on the island’s northeastern coast.

This phenomenon is not limited to Dominica: From the Bahamas to Barbados, China’s footprint is expanding through infrastructure, trade and diplomatic engagement.

A 2020 U.S. House Foreign Affairs Committee report found that Chinese trade with the Caribbean reached $8 billion in 2019 — an eightfold increase from 2002. Between 2005 and 2022, China invested more than $10 billion across six Caribbean countries, including $2.2 billion in Jamaica alone. In the Bahamas, Beijing has poured $3.4 billion into the Freeport Container Port, just 87 miles from Florida’s coast. These investments are often packaged within the Belt and Road Initiative, China’s sweeping global infrastructure program that now includes several Caribbean nations.

China’s appeal in the region isn’t limited to economics: Caribbean governments increasingly view infrastructure development as intrinsically linked to climate resilience, with roads, bridges, and ports seen as tools for mitigating the effects of rising seas and intensifying weather events.

Beijing has strategically adapted its rhetoric to these concerns, positioning its investments as contributions to climate adaptation — especially as the U.S. has been perceived in recent years as retreating from global climate leadership.

“Caribbean people view infrastructure and climate as intertwined,” says Leland Lazarus, associate director at Florida International University’s Jack D. Gordon Institute and a former U.S. diplomat. “When China builds a road or a bridge, they see it as helping with climate mitigation.”

Strategic considerations also loom large: U.S. officials have repeatedly raised alarms over China’s growing presence in what has long been considered a vital security zone.

In a 2023 testimony to the Senate Armed Services Committee, General Glen D. VanHerck of U.S. Northern Command described the substantial commercial and other presence of the People’s Republic of China in the Bahamas as “efforts to gain a foothold only 50 miles from the U.S. East Coast.”

Dr. Evan Ellis, research professor at the U.S. Army War College, sees China’s engagement as a calculated move to establish strategic support points that could serve both commercial and potential military purposes: “First of all, China’s engagement in the Caribbean is strategic, far beyond the economic interests that it pursues there.”

These concerns are far from abstract, with Chinese state-owned enterprises having donated military vehicles and equipment to Caribbean security forces, including police motorcycles in Guyana and uniforms for Jamaica’s Defense Force.

Though described as nonlethal aid, the symbolic and practical implications are significant: China is building long-term relationships with regional militaries, police forces, and political elites.

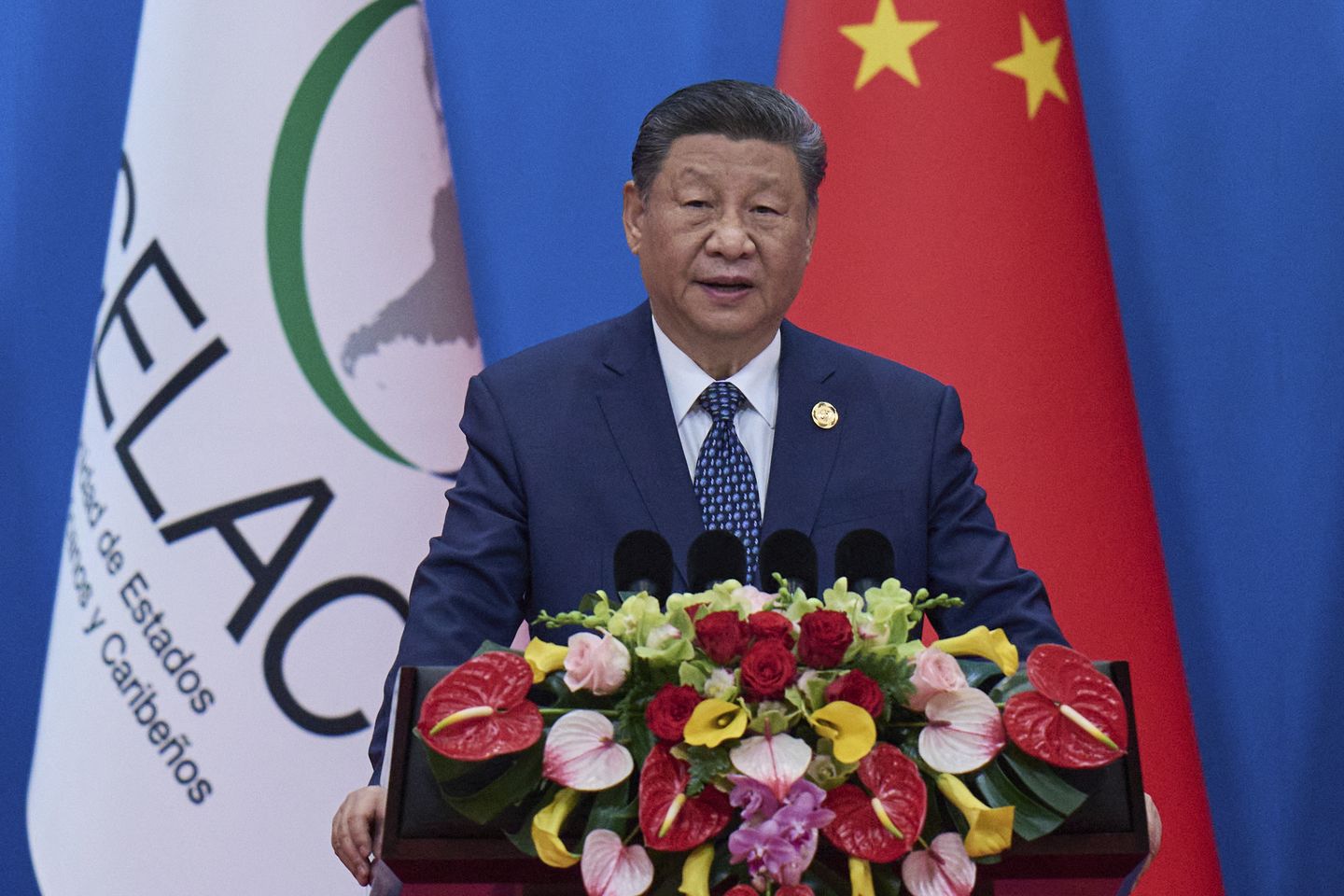

Diplomatic engagement has also accelerated. In January 2025, Chinese President Xi Jinping met with Grenada’s Prime Minister Dickon Mitchell and pledged deeper cooperation with Caribbean states. Around the same time, the Bahamas’ Prime Minister traveled to Beijing for the opening ceremony of the China-CELAC Forum.

These high-level meetings are now routine, offering Chinese leaders an opportunity to court allies in Washington’s traditional sphere of influence.

By contrast, Caribbean leaders often find themselves sidelined in Washington. “When Caribbean leaders go to Beijing, they get the red carpet,” says Lazarus. “In Washington, they’re often relegated to meetings with undersecretaries. Optics matter.”

With five of the 12 states in the world that continue to recognize Taiwan located in the Caribbean — those being Belize, Haiti, St. Vincent’s and the Grenadines, St. Kitts, and Saint Lucia — the region is also a battleground for Beijing’s ongoing campaign to diplomatically isolate Taipei. Dominica was among those aforementioned nations until 2004, when it broke ties with Taiwan in exchange for a $12 million aid package from Beijing. Since then, China has actively lobbied other Caribbean nations to follow suit, often targeting opposition parties and offering development assistance in return for diplomatic recognition.

Despite this, U.S. economic and diplomatic engagement is far from absent: Trade between the U.S. and Latin America and the Caribbean still surpasses China’s, and U.S. investments remain dominant in sectors like banking and tourism.

Meanwhile, the U.S. military’s Southern Command maintains defense partnerships with multiple Caribbean militaries and regularly conducts joint training exercises in the region, most notably the annual “Tradewinds” exercise, held every year since 1984.

Yet visibility matters, says Leland Lazarus. “The U.S. still outweighs China in terms of trade and investment, but I would argue that Chinese investments in the region are much more visible. You can’t really see some of the stuff that the US is doing, but you can see a road, or a bridge, and you can drive on them.”

Efforts to reassert U.S. influence are underway.

Secretary of State Marco Rubio made the Caribbean his first overseas stop in office, the first time in a century that an American top diplomat has done so. In May, he met with leaders from Saint Vincent, Dominica and other island nations, pledging renewed engagement and respect.

Still, analysts caution that a more consistent, respectful, and strategic approach will be needed to match Beijing’s momentum, as China embeds itself further in the region’s infrastructure, politics, and strategic calculus. As the U.S. and China jostle for influence in the Caribbean, Dominica offers a vivid case study: a small island caught in the currents of great-power competition, where the future of regional sovereignty and global alignment may be quietly shaped — one airport, one port, and one handshake at a time.