Fort Ticonderoga, located in northeastern New York, sits on a strategic peninsula at the confluence of Lake Champlain and Lake George, nestled between the Adirondack Mountains of New York and the Green Mountains of Vermont.

In 1775, it was the gateway to Canada and controlled the vital strategic waterways of Lakes Champlain and George. An American expeditionary force of about 200 Continentals, led by the legendary Ethan Allen and 100 of his Green Mountain Boys, along with a Massachusetts colonel named Benedict Arnold, who commanded about 60 militiamen, snuck up on the fort just before dawn on May 10, 1775, and overwhelmed the 80 British soldiers guarding it without firing a shot.

It was America’s first victory of the Revolutionary War. Meanwhile, George Washington had taken command of the army surrounding Boston. In truth, it wasn’t much of an army. The Americans lacked any significant military equipment, including artillery. Washington’s plan to besiege Boston wouldn’t work without artillery.

There were plenty of excellent artillery and all the cannon balls and powder that Washington would need at Fort Ticonderoga, but those supplies may as well have been on the surface of the moon. It was 300 miles through the Northern New York and New England wilderness from Ticonderoga to Boston.

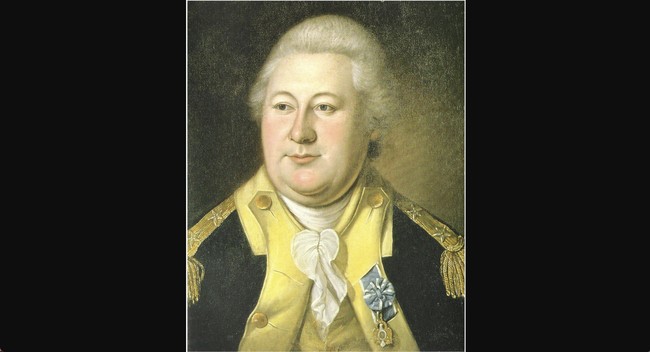

Henry Knox, often described as a “bookseller,” was a volunteer in Washington’s army. He boldly approached the general and confidently told him he could get Ticonderoga’s guns and bring them to Boston.

The Free Press’s Jonathan Horn describes the man who played a major role in winning the war.

In our era of credentialism, 25-year-old Henry Knox would never have made it to the interview stage for the position of artillery commander in the Continental Army. A look at his résumé would have shown he had dropped out of school, joined a street gang, gotten wrapped up as a witness in a prominent trial for soldiers accused of firing into a crowd (the Boston Massacre), worked as a bookseller, gone parading in a militia uniform, and wed the daughter of a high-ranking British official. If all that wasn’t enough to kill his chances, there was also this: He had ballooned to more than 250 pounds and accidentally shot off two of his own fingers.

Fortunately for America, General George Washington filled the opening based on talent rather than HR dictates or Pentagon mandates against “fat” commanders. On January 18, 1776—250 years ago this week—the trust in Knox paid off when he arrived at the Continental Army’s headquarters in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in advance of what he called a “noble train of artillery” carrying what many had thought immovable: the guns of Fort Ticonderoga.

Knox set off on his impossible journey in early December 1775 with sixty tons of artillery, powder, and shot. He “made forty-two exceeding Strong Sleds & has provided eighty Yoke of oxen to drag them as far as Springfield,” he wrote Washington after crossing Lake Champlain.

Knox had absolutely no experience with moving large bodies of men or equipment, but Washington made him commander anyway. It’s not just a testament to Washington’s genius but also the genius of America that a man like Knox could be plucked from obscurity to perform one of the most incredible feats of the entire war.

The artillery train arrived shortly after Knox’s appearance at headquarters on January 25. It took another five weeks for the cannon to be assembled and placed, and the powder to be distributed. By March 2, 1776, the British General Thomas Gage woke to the astonishing spectacle of 78 cannon looking down on him from Dorchester Heights. The guns not only threatened his troops but also the British ships in the harbor. Gates negotiated an exit from Boston by promising not to burn the city if Washington held his fire.

Knox was all of 25 years old when the war broke out. He went on to achieve the rank of general and demonstrated his genius again by engineering the crossing of the Delaware River on Christmas night, 1776. He engineered the river crossing back to Pennsylvania and then back to New Jersey to fight the battle of Princeton.

Knox’s war record would be enough to recommend him to history. And yet, after the war, he served as secretary of war under the Articles of Confederation and later, as the first secretary of war in American history under Washington.

Self-taught, self-made, a man of little schooling who ended up an artillery genius by reading books about war and applying his innate common sense to problems, Henry Knox was the quintessential American. We remember his stupendous feat of bringing his “Noble train of artillery” to Washington through 300 miles of dense wilderness against impossible odds, 250 years ago this week.

The new year promises to be one of the most pivotal in recent history. Midterm elections will determine if we continue to move forward or slide back into lawfare, impeachments, and the toleration of fraud.

PJ Media will give you all the information you need to understand the decisions that will be made this year. Insightful commentary and straight-on, no-BS news reporting have been our hallmarks since 2005.

Get 60% off your new VIP membership by using the code FIGHT. You won’t regret it.