SEOUL, South Korea — South Korean President Lee Jae-myung heads to China Sunday ahead of a Monday summit with President Xi Jinping in Beijing, where issues such as relations with Pyongyang, a Chinese ban on K-pop and maritime tensions in the Yellow Sea are likely to be on the agenda.

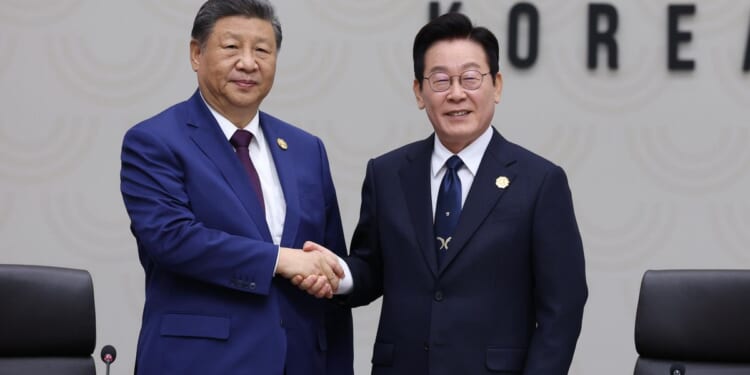

It will be their second powwow. The two leaders first met for a jocular meeting on Nov. 1 on the sidelines of the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation, or APEC, summit in South Korea, where Mr. Lee also met U.S. President Donald Trump.

Seoul constantly struggles to balance its security alliance with Washington with its economic ties with Beijing.

“In the security domain, cooperation with the United States is an unavoidable reality for us,” Mr. Lee told Chinese state broadcaster CCTV in an exclusive sit-down on Saturday. “However, this does not mean that South Korea-China relations should head towards confrontation or conflict – that would bring absolutely no benefit to South Korea’s national interests.”

Mr. Lee’s oft-stated desire to upgrade relations with China has garnered suspicions among U.S. conservatives, who will likely be watching him closely in Beijing.

However, his open posture means that, of all the democracies and U.S. partners on China’s periphery, Korea is best positioned to get an amicable hearing from Mr. Xi. Beijing’s regional relations elsewhere are dire.

China last week conducted extensive war games around Taiwan, emblematic of its hostile stance against President Lai Ching-te.

It is infuriated with Japan, where Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi suggested in November that a naval contingency around Taiwan would compel Tokyo to activate its own military.

And it continues to pour maritime militias, Coast Guard and naval assets into waters west of the Philippines, generating enmity in Manila.

“I hope this interview allows the public to see how much the [South Korean] government values relations with China,” Mr. Lee told CCTV. “The purpose of this visit to China is to minimize or eliminate past misunderstandings and frictions, advance relations to a new stage, and firmly establish a partnership in which both sides support each other’s development.”

Korea hosts around 28,000 U.S. troops to deter its northern neighbor. However, most are based on the country’s China-facing Yellow Sea Coast.

Pundits have made clear the usefulness of this deployment in any Taiwan contingency — an issue that is ultra-sensitive for Seoul, always reluctant to discuss the use of U.S. forces in Korea for regional operations.

In a media briefing last week, Mr. Lee’s National Security Adviser Wi Sung-lac repeated Seoul’s position that it cleaves to the “One China” policy favored by Beijing.

While Washington’s troops and nuclear umbrella save Seoul untold billions in defense costs, while underwriting its national security and its sovereign credit ratings, Korean commercial interests have taken hits as a result of the alliance.

Washington’s policy of limiting semiconductor technologies to China has impacted Korean chipmakers, unable to export high-end fabrication equipment to their plants in China.

In 2017, Beijing, furious that U.S. troops had established a THAAD anti-missile system in Korea, complete with powerful radars that can scan China’s atmosphere, retaliated economically.

Chinese tourism to Korea plunged, Hyundai saw Chinese car sales plummet and Lotte pulled out of China’s retail sector. Moreover, Chinese imports of “Korean Wave” products, notably K-pop and K-dramas, evaporated.

Unblocking the Korean Wave’s flow to China’s huge customer base is a Seoul priority.

“China’s official position is that there is no such thing as a ‘Korean Wave ban,’” Mr Wi told local press. “The understanding of the situation from the Korean government is different.”

Given the magnetic lure of the Korean Wave to Chinese consumers, one expert reckons Beijing leveraged THAAD to give domestic players breathing space.

“The ascendency of [the Korean Wave] in China had been sticking in China’s craw,” said CedarBough T. Saeji, who teaches Korean Studies at Pusan National University. “What THAAD accomplished for China was to redirect the Chinese consumer to China’s cultural products, to remove much of the Korean competition — and that, frankly, has been a huge success.”

Import substitution granted Chinese producers time to raise their game to the point that “…if the soft ban is fully lifted, Korean content will never be able to secure the size of the market it had in the past,” Ms. Saeji said.

Another contentious issue is China’s installation of structures in a sector of the Yellow Sea known as “The Provisional Measures Zone” between the two countries. They include 13 huge buoys, an oil rig-like platform and aquaculture cages.

Per a 2001 bilateral agreement, installations in the PMZ should be mutually discussed, but China has unilaterally established them, and patrols them with its Coast Guard, keeping Korean vessels at bay.

Some Koreans fear Beijing has initiated a creeping maritime takeover similar to what it has conducted in the South China Sea. Veterans’ groups have protested outside China’s Seoul embassy.

“I don’t care what the structures are, I care that they were supposed to talk to us about them,” fumed Chun In-bum, a retired South Korean general. “Instead, there was total disregard! This does not build trust.”

On other issues, Beijing and Seoul converge. Take North Korea.

While Mr. Xi seeks stability on his strategic northeastern flank, Mr. Lee wants to talk to a dismissive Pyongyang. Given that the recent U.S. National Security Strategy neglected mention of Korean Peninsula denuclearization, Beijing and Seoul have common ground.

“As far as denuclearization of the Korean peninsula goes, China still maintains, at least superficially, that objective,” said Lee Soon-chun former chancellor of the Korea National Diplomatic Academy. “We should try to persuade the U.S. to have this objective, otherwise there is too much pressure on us to make nuclear bombs ourselves.”

That, combined with the chummy APEC vibes, suggests China may be willing to play nice.

“The Chinese know that we are in an alliance with the U.S., but they also think they have a chance with the Lee administration,” said Mr. Chun. “As long as they think that, we have some leeway.”

Beijing’s strained relations with other U.S.-friendly nations in the region are a further factor.

“The fact that Lee is getting a one-on-one with Xi says a lot,” Mr. Chun reckoned. “The Japanese prime minister is not getting one, right?”