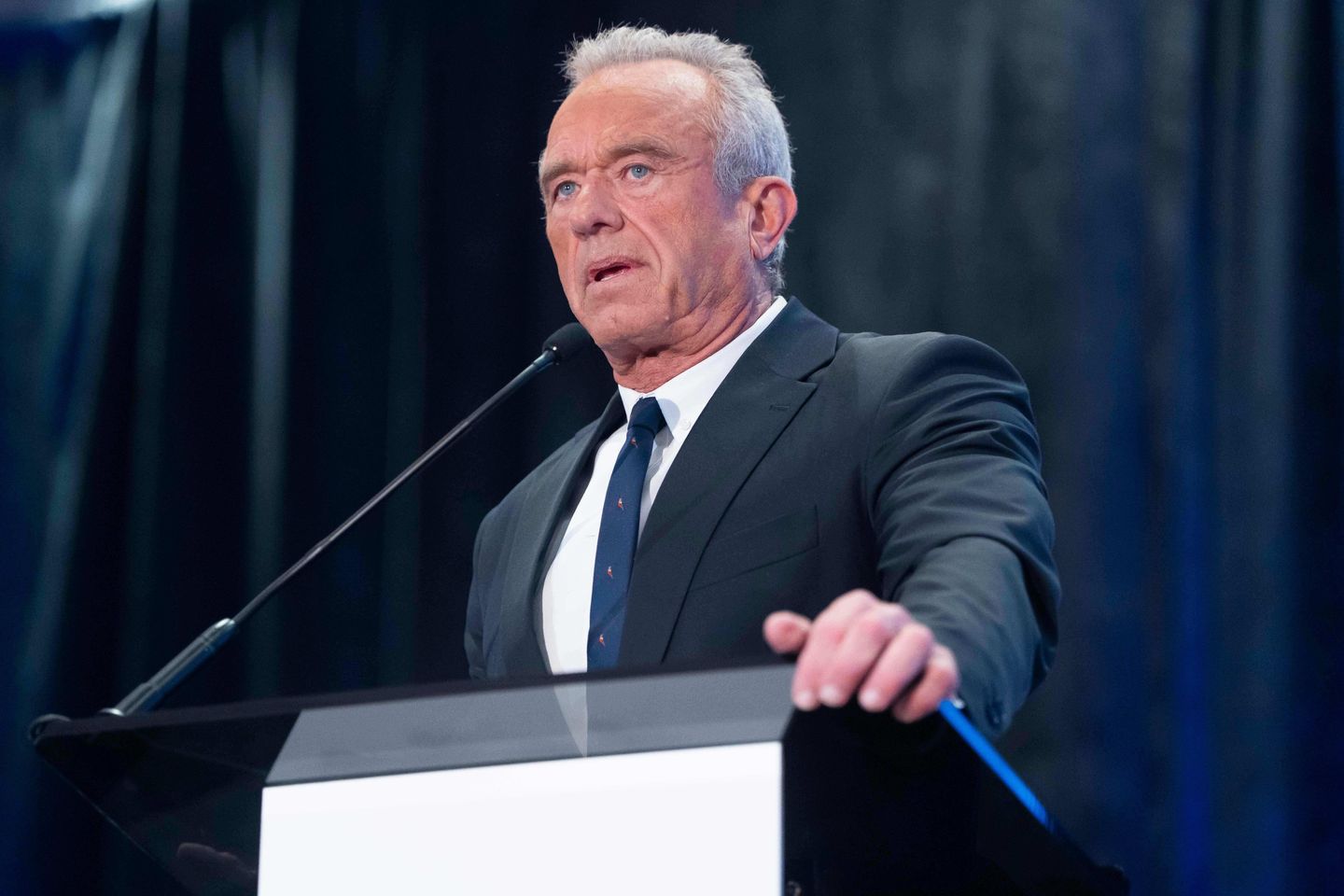

Federal advisers voted to abandon the long-standing hepatitis B vaccines for newborns — a milestone in Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s challenge to vaccines.

The hepatitis B vaccine — given to newborns within 24 hours of birth, known as the birth dose — is now recommended for infants starting at 2 months after birth.

The recommendation was approved despite objections from medical groups, doctors and lawmakers.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted 8-3 for the recommendation, suggesting that if the mother tests negative for hepatitis B, the child’s first dose should be delayed to two months.

The panel said a doctor should be consulted about whether or when to begin administering the three-dose vaccine series.

The vaccine protects against the contagious, incurable, liver-damaging disease. In adults, hepatitis B is typically shared through sexual intercourse or sharing of needles for drug use, but it can be passed from mother to baby.

The Friday recommendation could bring about changes to the childhood vaccination schedule by delaying the immunization routinely given to newborns.

The committee, handpicked by Mr. Kennedy, administered the recommendation after a two-day meeting. The panel was originally slated to vote on the vaccine in September before tabling it for Thursday, when it was delayed yet again.

Mr. Kennedy fired all 17 members of the committee in July, instead tapping eight replacements, some of whom are vaccine skeptics.

In June, Mr. Kennedy claimed that the shot at birth is a “likely culprit” in autism.

“If you are a baby that was born to a mother that was tested negative for hep B, you need to realize, as a parent, that your risk of infection throughout your early stage of life and probably throughout most of your childhood is extremely low,” committee member Retsef Levi said during the Friday meeting.

While the committee cannot make legally binding recommendations, its guidance is for the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on how approved vaccines should be used. Directors mostly adopt the committee’s recommendations.

Its decisions influence whether private insurance and government assistance programs, such as Medicaid and Medicare, cover the vaccines. As long as the hepatitis B vaccine remains approved by the Food and Drug Administration, insurance will continue to cover the cost of the shot.

Many state vaccination policies are directly linked to the committee’s guidance, and states have the authority to mandate immunizations.

Families can also choose to vaccinate at birth, later in childhood or not at all.

This change will have “deadly consequences for our children,” Dr. Tom Frieden, a former CDC director, said on social media before the decision.

The hepatitis B vaccine is up to 90% effective at preventing infection from the mother, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics. If babies receive the full three-dose vaccinations, 98% have immunity to the illness.

He is not the only medical professional concerned about delaying the birth dose.

“Delaying the first hepatitis B vaccine dose beyond the newborn period introduces risks that have lifelong detrimental consequences and no measurable health benefit,” specialists wrote in a Wednesday article in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Sen. Bill Cassidy, a physician and the chair of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, has frequently voiced his worries about changing hepatitis B vaccine guidance.

On CBS’ “Face the Nation” last month, the Louisiana Republican said this policy would be made by “people who don’t understand the epidemiology of hepatitis B.”

“The ACIP is totally discredited,” Mr. Cassidy said on social media Wednesday. “They are not protecting children.”

Aaron Siri, a vaccine injury lawyer who’s advised and represented Kennedy, presented during the meeting, prompting condemnation from Mr. Cassidy.

Mr. Kennedy has gone after vaccine recommendations before.

He recently announced the removal of the COVID-19 vaccine from the official CDC-recommended immunization schedule for healthy children and pregnant women, citing a lack of clinical data. This change created potential barriers to access, as insurance coverage for these groups is no longer guaranteed.