Though many do not like to admit the unpleasant truth, it is known that Lincoln supported what was called “colonization,” aka deportation, the returning of freed slaves to places far from America’s shores like Haiti, Panama, Honduras, and Liberia, the latter purchased by the American Colonization Society, of which Lincoln was for a time a manager, for the express purpose of offloading American Blacks.

Lincoln was indeed an unabashed proponent not only of “colonization” but also of the Free Soil Party. As history professor and Director of the War and Society Program Kyle Longley writes, “While not embracing abolition [but] instead ‘free soil’ (which called for preventing the expansion of slavery into new territories [to preserve white uniformity]), Lincoln also supported Whig leaders including [his mentor] Henry Clay, in calling for the resettlement of freed slaves in Africa.” In later years, he appears to have bethought himself, Longley argues. Longley’s dissertation adheres to many of the authentic facts about Lincoln, but it is plainly an intemperate and unmediated panegyric for Lincoln, which in context renders it also somewhat dubious.

Phillip Magness and Sebastian Page’s Colonization after Emancipation: Lincoln and the Movement for Black Resettlement tells a complicated but necessary story. Historians and journalists now praise Lincoln’s famous Jan. 1, 1863, Emancipation Proclamation for tamping down the colonization movement, changing the legal status of millions of slaves, and focusing the war effort on the abolition of slavery. The problem is that the Proclamation saw the light approximately two years after hostilities had begun and applied only to the rebellious territories where Lincoln had no authority, while the North was exempt, and many states were granted immunity. It was largely a symbolic and wholly cynical gesture to garner support for the Union cause, but it did not free a single slave. The colonization movement held its ground.

In an Aug. 14, 1862, conference at the White House with a group of freed slaves, true to his anti-black sentiments, Lincoln exhibited what today we would call unashamed racism, claiming, among other such fricatives, that “on this broad continent not a single man of your race is made the equal of a single man of ours.”

AI tells us that Lincoln “treated black voters to the White House with respect and dignity,” which, as we note, is simply not true. Caveat lector. Elsewhere, Lincoln states, “A separation of the races is the only perfect preventive of amalgamation, but as an immediate separation is impossible, the next best thing is to keep them apart.”

As the New York World put it, “He has proclaimed emancipation only where he has notoriously no power to execute it.” Indeed, for the first approximately two years of the war, the abolition of slavery was not the epochal issue, neither for the North nor the South. Lincoln was no abolitionist.

Earlier, as president-elect, Lincoln had supported a proposal that “no amendment shall be made to the Constitution, which will authorize or give to Congress the power to abolish, or interfere within any State, with the domestic institutions thereof, including that of persons held to labor or service by the laws of said State.” Which is to say, slavery. This was called the Corwin Amendment, about which Lincoln declared: “Holding such a provision to now implied Constitutional law, I have no objection to its being made express and irrevocable.” Only the War scuttled the amendment.

Is there any indication, then, as Christopher Shelley claims in The True Blue Federalist, that “Lincoln’s proximity to blacks helped to free him from his prejudice, and helped him to see blacks as something like full-fledged Americans”? Would Lincoln have said, as did Barack Obama with regard to same-sex marriage, that his views were “constantly evolving”? I have not seen any truly convincing evidence of Shelley’s thesis in Lincoln’s voluminous papers.

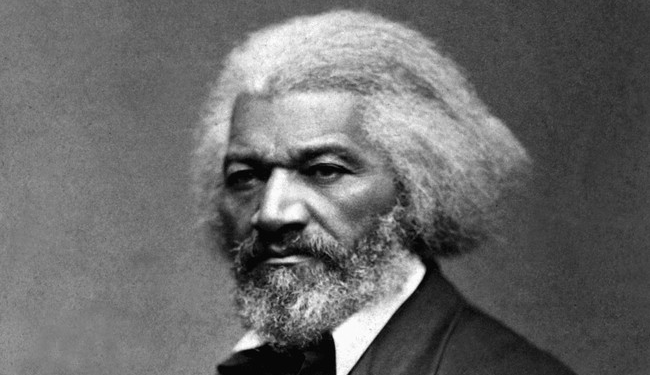

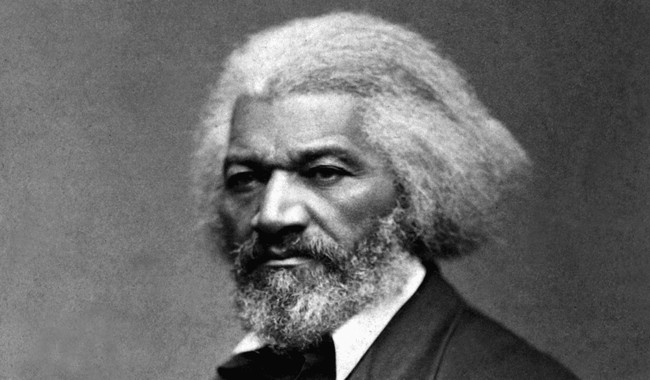

Many have claimed that Frederick Douglass, the celebrated black orator of the epoch, had earned Lincoln’s respect and caused the president to soften and alter his views concerning Blacks. There is some truth to this assertion, but the relationship between the two men remained complicated. Douglass, who was, like Obama, half black/half white, had a foot in both communities, was lessoned in part by his slave-owner mistress, and bore the looks with its Caucasian flair that would endear him to whites. A commanding and persuasive oratorical voice didn’t hurt either.

“Douglass had been disarmed to an extent by his host’s unpretentiousness and received a political education of a kind,” wrote Lincoln-enthusiast, Yale historian David Blight in his 2018 biography Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, about the first meeting between the two men. “Lincoln too had perhaps learned something of how a Black leader felt about the war… and the inhumanities they endured to fight it. The president might also have sensed for future reference how this brilliant radical pragmatist sitting with him that morning might be useful to the nation’s survival.” In any event, a mutual relationship does seem to have been established.

In a speech shortly after Lincoln’s assassination, Douglass said. “Whosoever else have cause to mourn the loss of Abraham Lincoln, to the Colored people of the Country his death is an unspeakable calamity.” Yet, on the 11th anniversary of Lincoln’s death in 1876, Douglass delivered a speech at the dedication of the Freedmen’s Monument in Washington. Douglass reminded his audience of his disagreements with Lincoln over colonization, the treatment of black troops during the Civil War, and the president’s distressing Reconstruction plan. “He was ready and willing at any time during the first years of his administration to deny, postpone, and sacrifice the rights of humanity in the colored people to promote the welfare of the white people of this country,” Douglass pronounced. However, as noted, Lincoln may have bethought himself afterward. The issue remains ambiguous.

As time went by, Douglass confided to having acquired a certain degree of appreciation of Lincoln’s pragmatism and political savvy. Had Lincoln survived, the president may well have regretted his earlier lack of empathy and concern. This must be admitted as a possibility, but it cannot be confirmed as a datum. Lincoln remains perhaps the most enigmatic of American presidents, and his unblemished good faith cannot be assumed. The general tenor of his actions and declarations prompts a degree of skepticism or should even among his partisans.

There is no doubt, then, that Lincoln felt, over much of his life and presidency, that there was too much Africa in America, that he suffered what today is called “black fatigue.” But he also realized that such an admission would not help him win the war. And as noted, many believe that his relationship with Douglass may have caused him to dramatically, or at least partially, change his heart and mind. As I have argued, this is a hopeful assumption, but not an indisputable fact.

Lincoln’s final speech from the White House on April 11, 1865, offers limited support for black suffrage, focusing on “the very intelligent or those who serve our cause as soldiers,” who may deserve the franchise. We might posit, as a veiled reference, that Douglass was obviously among the “very intelligent.” What the future might have been was ended by John Wilkes Booth three days later. The evidence for Lincoln’s new direction is tantalizing but incomplete. It is both encouraging and adroit, both morally and politically, but his papers, so far as we can tell, do not explicitly warrant a sea-change in Lincoln’s sensibility.

The evidence for the reversal of Lincoln’s earlier ways seems predicated more on the omission of problematic expressions than on the commission of assuring convictions. In other words, the evidence is encouraging but not definitive. All we can do at this point is take a more or less educated guess and hope that Charles Dickens’ Third Ghost remains an NPC.