Every Friday (well, one day early this week), we hand the mic to a different fiction writer for a sharp, ground-level look at the culture we’re all living in. These aren’t stories — they’re insights from the storytellers themselves: the people who spend their lives studying character, conflict, and the deeper currents that drive human behavior. Each week brings a new voice, a fresh perspective, and a writer willing to look past the noise and say what they actually see.

Today’s post is by David and MaryLu Barrow, a husband-and-wife writing team. David is a descendant of William Bradford and Myles Standish and grew up on a Massachusetts farm that had been in the family since the early 1700s. As you might imagine, he was steeped in history from an early age. He met MaryLu in high school. The two wrote And Justice for All, Even Redcoats, about John Adams’ famous defense of British soldiers who fired into the crowd at the Boston Massacre — an event that cemented the American ideal that every man deserves legal defense in a court of law. They are working on their next book about the Pilgrims and those first hard years.

This Thanksgiving, as we gather around our tables, it’s worth remembering that our blessings rest on foundations laid long before 1776. The earliest seeds of America’s written Constitution were planted not in Philadelphia, but on the wind-swept shores of Cape Cod in 1620 and 1621, when a small band of Pilgrims forged compacts that would shape the very idea of self-government.

The tiny seed from which our nation sprang arrived on this continent fortuitously — or, if you believe as I do, by the very breath of God. The Mayflower, carrying both Separatist Pilgrims and “strangers” seeking new lives in the New World, left late in the season, bound for the northern reaches of the Virginia colony, today’s New York. But fierce autumn storms drove them off course. After several failed attempts to sail south, nearly wrecking on the Cape’s treacherous shoals, they anchored at last in the shelter of what would become Provincetown Harbor. Winter was coming fast; they would have to settle nearby.

Arguments soon erupted. The Mayflower passengers were outside the jurisdiction of their charter, and tempers flared. In Of Plimouth Plantation, William Bradford recalled:

…discontented and mutinous speeches that some of the strangers had let fall from them in the ship – That when they came ashore they would use their own liberty; for none had power to command them, the patent being for Virginia and not for New England, which belonged to another government, with which the Virginia Company had nothing to do.

Wiser heads prevailed. Nearly every adult male aboard signed a document that began:

In the name of God, Amen.

and continued:

…do by these presents solemnly and mutually in the presence of God and one of another, covenant and combine ourselves together into a civil body politick… and by virtue hereof to enact constitute and frame such just and equal laws, ordinances, acts, constitutions and offices, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient…

Those words — just and equal — echo down to us still. In them lie the early stirrings of due process and equal protection under law.

The Separatists were used to vigorous debate, believing that through discussion God would guide them to consensus. They elected officers to carry out these decisions, creating what would become the model for the New England town meeting, immortalized centuries later in Rockwell’s Freedom of Speech.

That first winter was brutal. Half of them died. Those who survived endured two more years of hardship and hunger before the modest celebration we now call the first Thanksgiving in the autumn of 1621.

Another colony, just north of Plymouth, wasn’t so fortunate. Lacking faith and any unifying compact, it descended into chaos and offended nearby tribes through theft and abuse. It survived only because of quick action by Plymouth’s military advisor, Myles Standish, and “a few good men.”

Standish deserves a closer look. A veteran of the Thirty Years’ War, he was a wiry redhead just over five feet tall, with a temper as quick as his sword. During the rescue of the northern colony, he killed a Massachusett warrior over six feet tall in single combat with the man’s own knife. The Wampanoags, allies of Plymouth, adored him. The Narragansetts and Massachusett learned to fear his name.

Hired to train the Pilgrims’ farmers and craftsmen into a militia, Standish was something like “Gunny” R. Lee Ermey of Full Metal Jacket fame — you did not want to drop your musket in front of him. Those “few good men” he drilled became the first of the militias that would spread through every New England town.

Fast forward 150 years. The habits of self-government born on the Mayflower had deep roots. When the British Empire, staggering under the costs of the Seven Years’ War, began taxing the colonies without consent, New Englanders bristled. The new taxes, admiralty courts, and writs of assistance weren’t just burdens — they were insults to a people used to governing themselves.

Protests mounted. The Boston Tea Party came and went. The Crown struck back, revoking the Massachusetts charter, closing Boston Harbor, and quartering redcoats among them under what became known as the “Intolerable Acts.” In response, the town meetings — descendants of the Mayflower Compact — called the people together, and the militias first trained by Myles Standish were ordered to make ready.

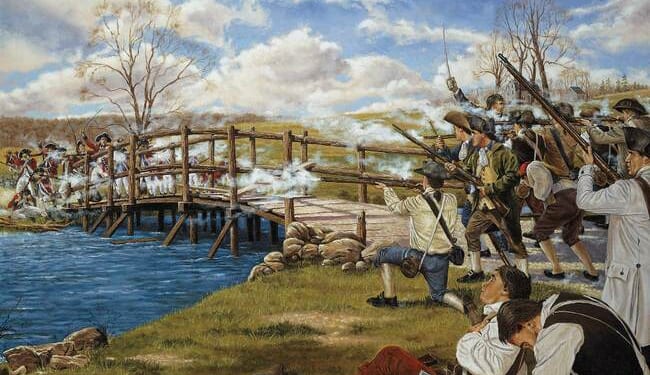

In April 1775, British troops marched to Lexington and Concord to seize colonial arms and arrest patriot leaders. Those militias stood their ground and fired “the shot heard ’round the world.”

Decades later, an old militiaman named Levi Preston was asked why he had gone out that morning. Was it the Stamp Act? The Tea Tax? Enlightenment ideals? His answer cut to the heart of it:

Young man, what we meant in going for those redcoats was this: We had always governed ourselves, and we always meant to. They didn’t mean that we should.

And so the covenant first written in cramped quarters aboard the Mayflower bore fruit in the Declaration and Constitution of a free people. As Governor Bradford would later write:

Thus, out of small beginnings greater things have been produced by His hand that made all things out of nothing and gives being to all things that are, and just as one candle may light a thousand, so the light here kindled hath shown unto many, yea in some sort to our whole nation.

Let’s not forget this Thanksgiving to give thanks to our Founding Fathers both for the sacrifices they made for us, their inheritors, and for the critical insight that for a people to govern themselves without a king, a contract had to be drawn up for everyone to agree to — a Constitution.