Washington’s foster-care crisis was so dire at one point that children were sleeping in hotels, state offices and cars, but state officials are turning away longtime Christian foster parents who won’t use children’s opposite-sex pronouns.

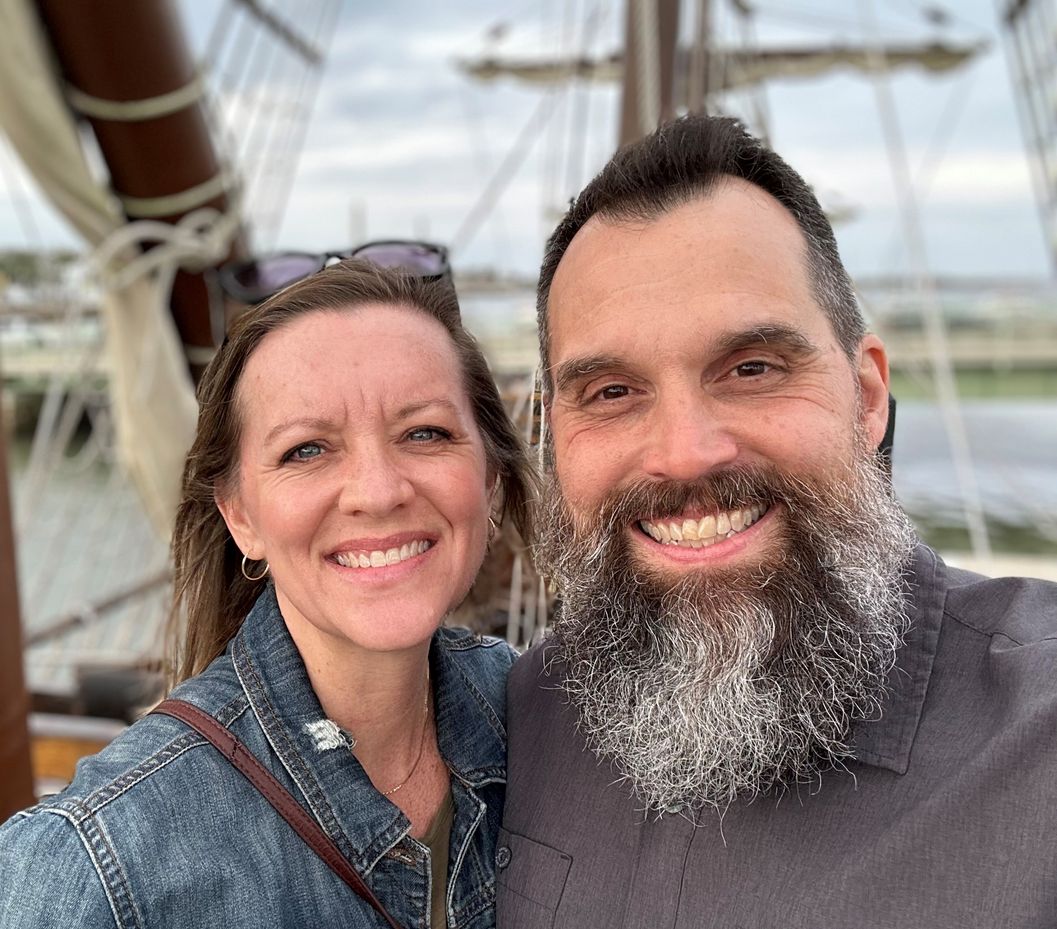

Shane and Jennifer DeGross sued officials at the Washington Department of Children, Youth and Families, accusing the agency of denying their license-renewal application over their refusal to abide by its policy requiring foster parents to use “the pronouns and chosen name” of transgender youth.

The regulations also require families to provide resources “that supports and affirms their needs regarding race, religion, culture, and SOGIE,” which stands for “sexual orientation and gender identity/expression.” Suggestions include displaying “Pride flags or similar indicators,” the lawsuit said.

“The DeGrosses are religiously motivated to provide foster care, and religiously motivated to live out their faith at home and express their religious views on human sexuality at home,” said the lawsuit filed Friday in U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington, Tacoma Division.

“But the Department conditions their ability to provide foster care on their willingness to do things that violate their religious beliefs, like using self-selected pronouns or taking a child to pride parades,” the complaint said.

The agency’s 2022 refusal to renew the DeGrosses’ license after nine years of fostering comes even though the state “continues to struggle with recruiting and retaining caregivers, specifically those with the skills, ability, and desire to parent children and youth with complex needs,” said the DCYF in a 2024 report.

The state acknowledged in 2021 that foster youth were spending the night in hotels and offices in the aftermath of a KING-TV expose. In some cases, children were placed in caseworkers’ cars without pillows or blankets to coerce them into accepting a foster placement.

“The placement resource crisis that leaves children in hotels and offices has continued to worsen over the past seven years, with the number of placement exceptions rising every year,” said the Office of the Family and Children Ombuds in the 2021 report.

The conflict over the state’s transgender rules appeared to be resolved in 2020, when the alliance won a federal court decision in favor of James and Gail Blais, a Seventh Day Activist couple denied a foster-care license over their refusal to abide by Policy 6900, the previous transgender policy.

The state discontinued Policy 6900, but replaced it with new regulations known as Section 1520, which is “substantially similar to Policy 6900,” the lawsuit said.

Jason Wettstein, DCYF communications director, told The Washington Times that as of September 2022, “we eliminated stays in offices, and there have not been car stays either.”

He declined to comment on the details of the ongoing legal dispute, but said that it is “well-documented that children and youth who identify as LGBTQIA+ have high rates of depression, anxiety, suicide, self-harm and eating disorders.”

“Whether a family accepts or rejects a child’s sexual orientation, gender identity or expression (SOGIE) has a profound impact on their wellbeing, and children and youth who identify as LGBTQIA+ are overrepresented among the foster care population,” he said. “In Washington, we are committed to ensuring that these vulnerable children and youth do not experience additional trauma when placed out-of-home into foster care.”

Regarding the Blais decision, Mr. Wettstein said that state officials “cannot and do not disqualify people from becoming foster parents on the basis of sincerely held religious beliefs.”

“However, the permanent injunction does permit DCYF to take an applicant’s views on LGBTQ+ issues into account when reviewing foster family home license applications or family home study applications,” he said.

In 2021, DCYF Secretary Ross Hunter declared that “Washington requires potential foster parents to accept ALL children and youth for who they are.”

“We do not grant licenses to families that are unwilling to be accepting of a child or youth who explores their sexual orientation, gender identity or gender expression and comes out while in their care,” he said.

Johannes Widmalm-Delphonse, ADF legal counsel, said that “Washington state officials are putting their own ideological agenda ahead of children who just need a loving home.”

“Despite the DeGrosses’ faithful service as foster parents for nine years, the state disqualified them simply for having views that Washington does not like,” he said. “As a federal court has already affirmed in Blais v. Hunter, this exclusion is unconstitutional — religious beliefs about human sexuality are not a legitimate or constitutional reason to categorically bar citizens from helping children.”

The DeGrosses apparently aren’t alone. A staffer at Olive Crest, a foster-care licensing agency that works with the state, told them that “there were other families who did not receive their licenses because they could not agree to the updated WACs [Washington Administrative Code rules].”

The DeGrosses have cared for four different girls as foster parents: a newborn, a two-year-old, another two-year-old, and a three-year-old, the complaint said.

“And until the DeGrosses sought to renew their license in 2022, the Department never raised any concerns about the DeGrosses’ capacity to care for foster children,” said the lawsuit.