After bilking hundreds of billions of dollars from Uncle Sam through bogus pandemic assistance applications, fraudsters have hit on a new target audience to scam: Each other.

Federal authorities say they have uncovered attempts to extort money from people by sending fabricated law enforcement documents warning targeted people that they face charges of pandemic fraud. But if they make a “preemptive bail” payment, the matter can go away.

Call it the scam within a scam.

One analyst said it’s been “deadly effective” at snaring folks because there was so much fraud in the original pandemic programs. That means there are a lot of people out there who got away with fudging their work history for unemployment or fabricating details on their application for a Payroll Protection Program loan.

“These people who cheated on their unemployment, cheated on their rental assistance, cheated on their PPP — they know they cheated,” said Haywood Talcove, CEO of government at LexisNexis Risk Solutions. “This is the call they have absolutely been dreading, and they are willing to write a check.”

The U.S. attorney in Oklahoma City said a version of the scam they’ve seen involves text messages with a fake federal court notice accusing the recipient of criminal pandemic fraud. They are told they can pay a “preemptive bail bond” to expunge the case.

The images bear indications to suggest they come from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.’s inspector general or the FDIC’s legal division.

“These fraudsters utilize fear and pressure tactics to create a sense of urgency in their victims and often prey on the most vulnerable in our society,” said U.S. Attorney Robert Troester, who said the best thing targets can do is to “not engage.”

Anand Ramlall, special agent in charge at the FDIC’s inspector general, said a giveaway that the texts are fraudulent is the request for payment through wire transfers, digital currency or gift cards. Government agencies just don’t do that, he said.

The U.S. attorneys in Wyoming and eastern Pennsylvania this week warned of scams aimed particularly at users of the PPP, which offered forgivable loans to small businesses so they could pay rent and salaries during the early days of the pandemic.

Those scam letters say the recipients are the subject of an arrest warrant but can “list” the warrant by making a payment at a cryptocurrency kiosk such as Coinflip, which relies on Bitcoin.

Mr. Talcove said scammers may also ask to be paid in gift cards, though some are sophisticated enough to take credit card payments.

He said the scams work because they hit so close to home for so many people.

“They’re nervous that they could be in trouble and they do pay,” Mr. Talcove said. “The problem is the fear. You’re scared out of your mind.”

He said the perpetrators are the usual actors, some domestic and some transnational, many of whom were themselves involved in pandemic fraud. “Now they’re going for another serving,” he said.

In some cases they’ve been able to obtain lists of people who obtained PPP loans or applied for pandemic-era unemployment, so they know the pool of targets.

There’s a bit of delicious irony in fraudsters being scammed by fraudsters, though it’s a bit like Orioles fans watching the Red Sox play the Yankees and wishing they both could lose.

Mr. Talcove said there are easy ways to deal with the calls if someone is a target, including just hanging up or ignoring the message.

If someone feels compelled to follow up, they should ask the caller for the main switchboard of the agency where they work. If the agent is legitimate, the switchboard can transfer the caller back to the investigator.

But Mr. Talcove said no government agency is going to reach out with a phone call and a demand for money. The process will start with a letter or, if the fraud crossed serious lines, a personal visit from agents.

Federal investigators are still grasping for a tally of the total fraud perpetrated in pandemic assistance programs, but acknowledge one may never be known.

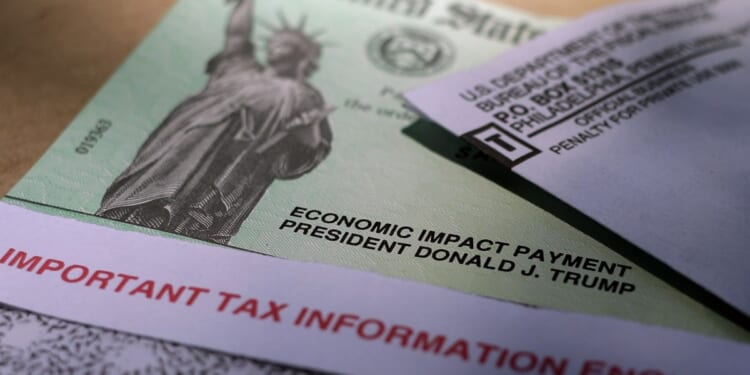

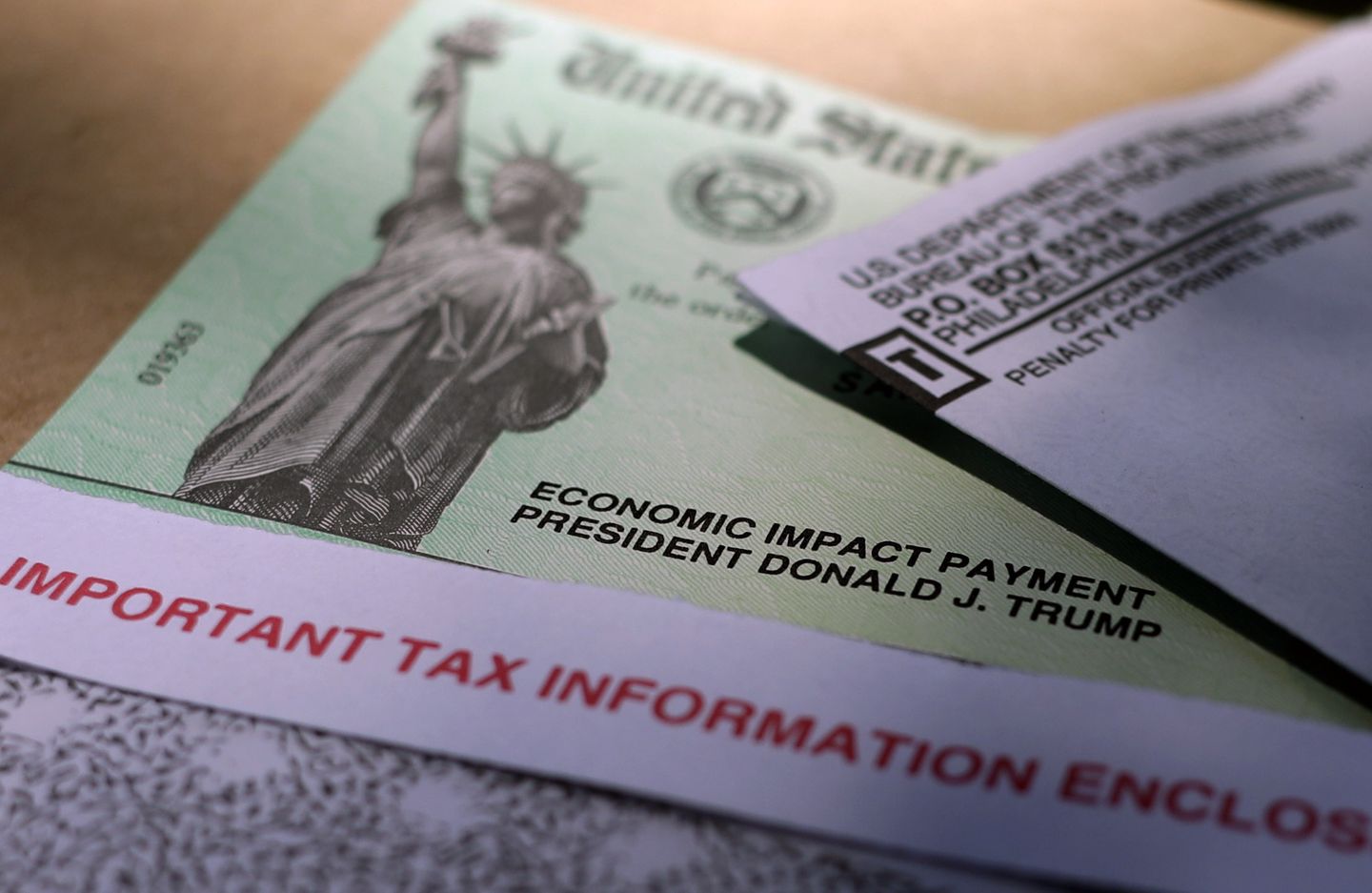

The big targets were the PPP and Economic Injury Disaster Loans, both run by the Small Business Administration, and expanded unemployment insurance, doled out by states but backed by federal taxpayers.

But rental assistance, restaurant stabilization and IRS stimulus payments were also bilked.

Frauds range from small — people who claimed a few weeks or months of unemployment checks despite not having been working before the pandemic, or still holding a job during it — to massive frauds that involved filing hundreds of applications and collecting tens of millions of dollars.

The single largest scam so far involved an Agriculture Department program designed to provide meals for kids who were out of school. Dozens of people in Minnesota have been charged with collecting money for meals that were never provided.

Prosecutors peg the cost of that scam at $250 million.

While some pandemic fraudsters have shown shame and contrition, others have blamed their deeds on the times, saying they were frightened about their finances and the government made it too easy to steal.

A few even cast themselves as Robin Hood do-gooders, saying they stole the cash to help family or communities back in the countries they emigrated from.

“In fact, not a single person lost any money,” Natalie Le Demola, convicted of taking part in a $1.7 million unemployment benefits scam from a prison cell where she was serving a term for murder, said in court filings to a judge ahead of her sentencing last year.

The judge gave her an extra seven years in prison.