SEOUL, South Korea — In a region overshadowed by China and North Korea, Washington has been keen to encourage the new cooperative spirit currently uniting Seoul and Tokyo, enabling the trilateralism U.S. defense planners have so long sought to project in the region.

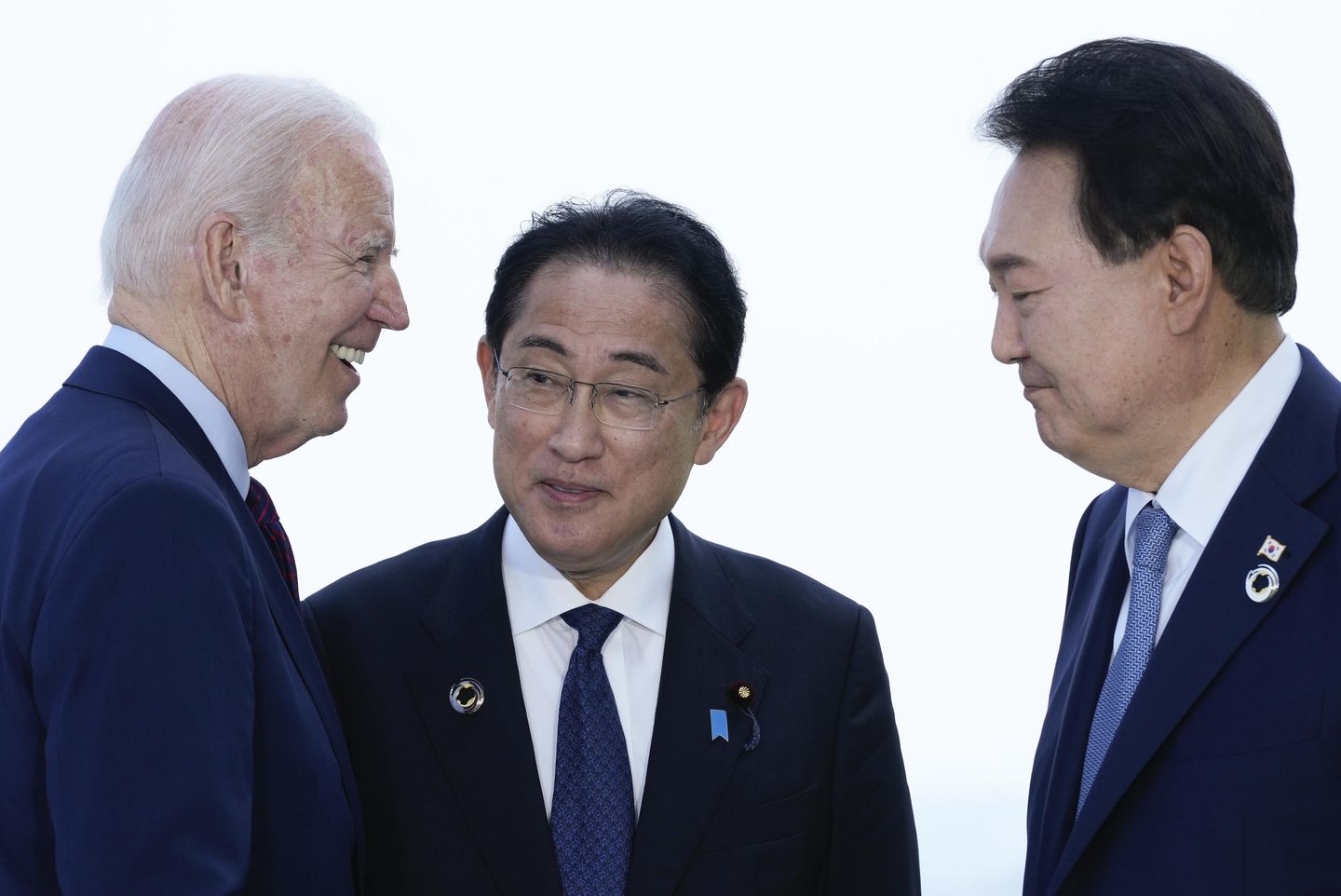

The voters in America’s two key East Asian allies, however, are far less pleased with their leaders these days. As both China and North Korea test American interests and allies across East Asia, the high hopes President Biden expressed at a precedent-breaking summit of the three leaders in Camp David in August could be sorely tested in the coming months.

Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida is reeling from a succession of party scandals, while South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol is facing fallout from questions over his wife’s behavior. Both are facing dangerously low approval ratings, but it is the South Korean leader who looks more vulnerable.

Mr. Kishida’s ruling Liberal Democratic Party, or LDP, is not facing a credible opposition and looks firmly entrenched in power in Tokyo, Japanese political watchers say.

Mr. Yoon’s People Power Party, or PPP, by contrast, is a minority in the National Assembly and could see its position eroded further in April’s general elections. That could leave the president politically crippled — with three years still to serve.

Ratings woes, wife troubles

The conservative Mr. Yoon won 2022’s presidential election by less than 1%. Facing an opposition-controlled house, the president, who had no prior diplomatic or overseas experience, surprised many in Seoul by focusing on foreign affairs early in his term.

His initiatives include patching up decades of historical ill feeling with former colonial power Japan, and creating a nuclear consultative group, as well as expanded nuclear protection from the U.S. against an attack from North Korea.

Now, with National Assembly elections looming, the scandal that has become known here as “Dior-gate” has engulfed his wife, Kim Keon-hee, at a very bad time for the government.

In a bizarre affair, a Christian pastor met Mrs. Kim and gave her a Dior handbag, worth $2,250, in 2022. She asked him the reason for the gift, but apparently accepted the bag. The pastor, whose aim in approaching Mrs. Kim was to try to win a meeting with Mr. Yoon to urge him to soften his hardline policy toward Pyongyang, filmed the meeting with a secret camera.

The news and footage broke last November, embarrassing Mr. Yoon, Mrs. Kim and the ruling PPP. In a rare TV interview earlier this week, Mr. Yoon accused the pastor of a “political maneuver.” But, instead of apologizing for his wife, he excused her on the grounds of her good nature, saying: “The fact that she was unable to coldheartedly reject him was the problem.”

The wording generated fresh controversy. The small opposition New Future Party accused national broadcaster KBS, which interviewed Mr. Yoon, of becoming “a PR agency for the president’s family.” The main opposition has had a field day, demanding an investigation into the actions of the South Korean first lady.

Low ratings are nothing new for Mr. Yoon, who was hovering around a 30% positive rating within months of taking office. But his latest ratings, 29%, combined with upcoming elections, could ignite a bigger political explosion.

“A lot of the public are gossiping about the Dior bag though it is not a big thing. It should not affect their personal or economic circumstances,” said Yang Sung-mook, a former foreign affairs advisor to the opposition. “But it will grow in the public mind.”

That is ominous. Former President Park Geun-hye, though unmarried, was fatally damaged by her tight relationship with a corrupt associate, Choi Soon-shil. Ms. Park ended up impeached, out of office, and jailed in 2017.

Mr. Yoon’s predecessor, Moon Jae-in, was also damaged politically by his close association with a friend he hired to reform the legal system. The friend, a colorful academic named Cho Kuk, not only lost the high-profile reform fight, but was himself embroiled in his wife’s controversies.

The big beneficiary of that scandal was then-Chief Prosecutor Yoon, who used the episode as a springboard to a campaign that gave him the presidency.

First ladies have proven problematic for previous presidents. Most notably, ex-President Roh Moo-hyun committed suicide after leaving office in 2009 amid a corruption probe that targeted his wife. After Roh’s death, the investigation was dropped.

Calling Mrs. Kim “a liability from the beginning,” Mr. Yang warned that momentum could build against Mr. Yoon. “If he loses the [April] general election, that could build up a loss to the next presidential election.”

That contest is not due until 2027, suggesting potentially weak leadership in Seoul for a prolonged period.

“A ‘lame duck’ president is usually the last few months or the last year in office, and it ties the president’s hands,” said Michael Breen, author of “The New Koreans.” “But this could be a ‘lame duck’ for three years,” with the opposition able to veto virtually all of his major proposals.

“If Yoon is going to face a so-called ‘vetocracy,’ we will see stalemate and confrontation between the presidential office and the assembly for three years and people will be exhausted,” said Lim Jong-eun, an expert on Japan and Korea relations at Kongju National University, who expects voters to elect a “patchwork” assembly in April.

“That is why the ruling party is really obsessed with this election,” she added.

In Japan, Mr. Kishida is facing what some consider the biggest political graft scandal in decades. Last year, a succession of LDP lawmakers and aides were found to be taking money raised from selling tickets to party events, paying it into party slush funds, then understating the amounts on their taxes.

Local press reports say 10 persons, including three lawmakers, are under scrutiny from prosecutors. Mr. Kishida has admitted that 37 lawmakers are correcting their personal financial records and statements.

The prime minister apologized publicly and removed implicated lawmakers from his cabinet last month, saying, “I humbly regret, and made a determination to have policy groups make a complete break from money and personnel affairs.”

The “ticket” affair follows an earlier imbroglio linking the LDP with the Unification Church.

In 2022, former Prime Minister and LDP icon Shinzo Abe was assassinated, and the killer alleged he acted because his family had been coerced into making large donations to the church more than a decade ago. The right-wing Mr. Abe had connections with the church, which espouses anti-communism.

That drew attention to linkages between the LDP and the Unification Church, which has reportedly mobilized members to support the conservative party during elections. In September 2022, the party revealed that nearly half of the members its surveyed had relations with the church and Mr. Kishida removed seven ministers with links to the church. The Japanese branch of the church, whose parent organization also owns The Washington Times, denies wrongdoing and is now battling left-wing critics who are trying to take away its tax-exempt status as a religious organization.

The double whammy of scandals is having an impact: A January poll found the approval rating for Mr. Kishida‘s Cabinet had fallen to 27%.

Yet, the LDP, which holds both the upper and lower houses of the Diet with a religious-based coalition partner, looks firm. The January poll found the LDP to have approval ratings of 31% — well ahead of the main opposition party, the Constitutional Democratic Party, with just 8%.

“Institutionally, it is very difficult to overthrow this huge giant, the LDP,” said Ms. Lim. “The Japanese Democratic Party don’t have real alternative ideas either and as long as they are not that popular, Japanese, who are quite conservative, tend to keep choosing the ruling party.”

While the LDP is secure, Mr. Kishida may not be: The party holds an internal leadership contest in September.