NEW YORK — Two men accused of killing Run-DMC’s Jam Master Jay were both close to the trailblazing DJ, but were driven by “greed and revenge” over a failed drug deal when they ambushed him at his recording studio more than 20 years ago, prosecutors argued as the men’s trial began Monday.

In opening statements in Brooklyn federal court, Assistant U.S. Attorney Miranda Gonzalez laid out the prosecution’s case that Karl Jordan Jr., the hip-hop star’s godson, and Ronald Washington, a childhood friend, killed the 37-year-old in 2002 after they were cut out of a lucrative cocaine deal. Both men have pleaded not guilty.

While the case languished for almost two decades until Jordan and Washington were arrested in 2020, becoming one of the hip-hop world’s most elusive mysteries, Gonzalez told jurors that they would hear from eyewitnesses who were in the studio that night, and that the pair confessed their involvement to others.

“Each defendant was proud that they had taken down Jam Master Jay and got away with it,” she said.

Washington’s lawyer Ezra Spilke, however, argued the case was held together with “tape and glue” and declared that prosecutors have “no clue” who killed Jay, who was born Jason Mizell.

“This case is about 10 seconds, 21 years ago,” he said. “It’s a blink of an eye, a generation ago.”

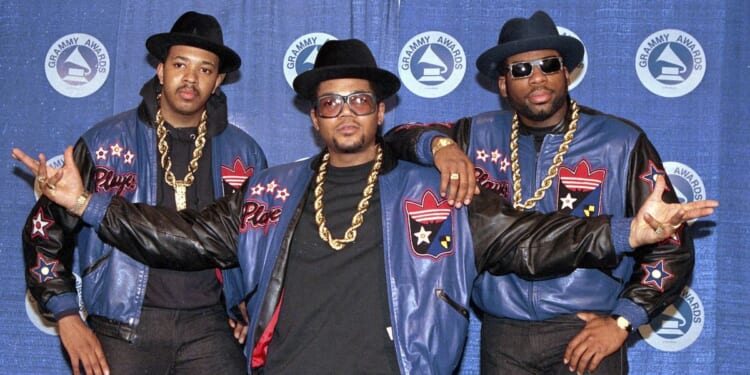

PHOTOS: ‘Greed and revenge’ drove 2 men accused of killing Run-DMC’s Jam Master Jay, prosecutors say

The men face at least 20 years in prison if convicted. The government has said it would not seek the death penalty.

Mizell worked the turntables alongside rappers Joe “Run” Simmons and Darryl “DMC” McDaniels as the group helped bring hip-hop into the mainstream in the 1980s with hits like “It’s Tricky” and a remake of Aerosmith’s “Walk This Way.”

Run-DMC famously espoused an anti-drug stance in lyrics and PSAs, but Gonzalez said that as the spotlight faded, Mizell turned to the drug trade, serving as a middleman to sellers and buyers across the country. A few simple calls, she said, could earn him “hundreds of thousands” of dollars.

Mizell had allegedly acquired 22 pounds of cocaine, which Washington, Jordan and others planned to distribute in the Baltimore area. But the dealer involved in the sale refused to work with Washington, cutting both defendants out of a potential $200,000 payday, she alleged.

Gonzalez said that in the days leading up to his death, Mizell acted troubled and carried a gun. On the night of Oct. 30, 2002, however, he barely had time to react when the two men and an accomplice, Jay Bryant, showed up at his studio in Jamaica, Queens. Bryant was charged last year after he was seen going into the building the night of the killing and his DNA was recovered at the scene. He will be tried separately.

Prosecutors say Washington waved a gun and ordered one person to lie on the floor, while Jordan shot Mizell in the head at point-blank range, killing him instantly. Another shot hit and wounded another man in the studio at the time, Mizell‘s friend Uriel “Tony” Rincon, before the killers fled, Gonzalez said.

“It was an ambush, an execution,” she said. “He was murdered in his own studio by people he knew.”

Still, police struggled to close the case because witnesses initially weren’t forthcoming. The people in the room at the time didn’t identify the killers for months even years later, Gonzalez said.

Lawyers for Jordan and Washington argued that the police still haven’t figured it out, and they urged jurors to be skeptical of witnesses who are cooperating in exchange for leniency on their own legal troubles.

Spilke, Washington’s lawyer, questioned why his client would want to kill Mizell since Washington was an alcoholic, relied on the rap star financially and was living on Mizell’s sister’s couch at the time.

“Why bite the hand that feeds you?” Spilke said.

In a Playboy article published a year after the killing, Washington was quoted as saying he was on his way to the studio the night of the killing when he heard gunshots and saw Jordan fleeing.

Washington’s lawyers also questioned Monday why none of the people with Mizell at the time of his death bothered to call police. Instead, Randy Allen, a friend and business partner who was among those in the studio, went directly to a nearby police precinct to report the shooting, they said.

Jordan’s lawyer John Diaz, meanwhile, said his client wasn’t even at the studio that night. His attorneys have said in court documents that Jordan, then 18, was at his pregnant girlfriend’s home at the time of Mizell‘s death and that witnesses can place him there. He was first named as a possible suspect in the slaying in 2007, while he was on trial for a string of armed robberies, though he maintained he had no involvement.

Jordan also faces gun and cocaine charges in the trial to which he has pleaded not guilty. While he has no prior adult criminal record, prosecutors allege he has continued to be involved in narcotics trafficking and say they have footage of him selling cocaine to an undercover agent.

The trial will resume Tuesday after the jury heard Monday from three police officers, including crime scene investigators who collected evidence and a detective who was among the first on the scene.