Some regional public universities are bracing for a fresh round of humanities cutbacks in 2024 as more financially conscious students shun degree programs associated with low-paying careers.

The expected cutbacks follow on the heels of belt-tightening last year by U.S. colleges facing dwindling enrollments, state budget reductions, rising costs and a shrinking pool of applicants. History, languages, arts and literature programs have taken the biggest hits since COVID-19 shuttered campuses in March 2020.

Higher education leaders from New York to Kansas have cited holes in their state-subsidized budgets as the main reason for eliminating programs. They are scrambling to promote business, science, math and technology degrees that students associate with better-paying jobs.

“It’s not surprising to see students looking for what they consider ‘practical’ courses for their careers,” said Ronald J. Rychlak, a law professor and former associate dean at the University of Mississippi, which has not made cuts.

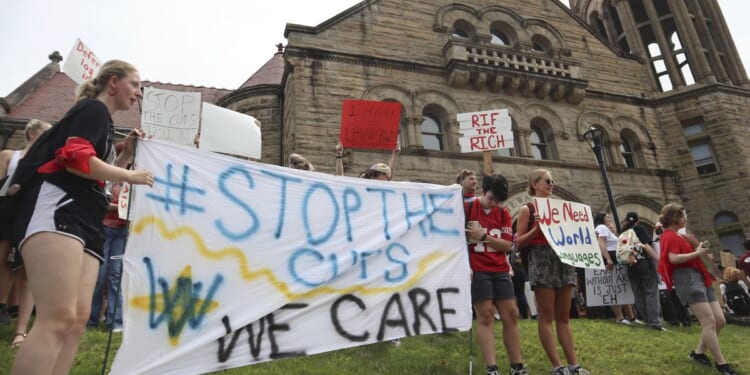

— In Morgantown, West Virginia, where the state’s flagship West Virginia University voted last year to eliminate at least 143 faculty positions and gut foreign language offerings, Provost Maryanne Reed told a faculty meeting this month that more cuts could be coming soon. Officials are also considering cutbacks at two of WVU’s regional campuses, Potomac State and WVU Tech.

— The State University of New York at Potsdam is phasing out nine academic programs over the next 3-4 school years. They include art history, dance, French, philosophy, Spanish and theater majors.

— Dickinson State University has asked the North Dakota State Board of Higher Education to approve plans to lay off five professors and eliminate seven low-enrollment degrees — communication, political science, music, theater, mathematics, math education and information analytics — to overcome a $1 million budget hole.

— Sometime this year, regents with the University of Kansas system will announce which programs they plan to consolidate or eliminate at its six state campuses.

While faculty and students loudly protested the cuts last year, some campuses have fallen silent this month as critics returning from winter break quietly weigh the future of their doomed programs.

“There are a range of opinions on this process, as it is by design a difficult one to go through and these decisions are not something we have arrived at lightly,” Mindy Thompson, associate vice president for communications at SUNY Potsdam, told The Washington Times.

Ms. Thompson noted that the campus in northern New York is “completing a strategic planning process to focus our energies and resources toward what’s most important to student success on our campus,” with an eye toward redirecting funds to “areas of promise and growth.”

According to the Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics, the share of bachelor’s degrees that four-year colleges granted in the humanities fell from 16.8% of sheepskins in the 2010-11 school year to 12.8% in 2020-21.

In West Virginia, an American Academy of Arts and Sciences study found humanities graduates earned $56,841 on average each year, while education majors earned $49,189 and arts majors $40,167. By contrast, engineers averaged $91,646 and high school graduates $39,351.

R. Scott Crichlow, a tenured political science professor and faculty senator at WVU whose job is not in danger, emphasized that humanities graduates in the state still earned 40% more than workers with only a high school diploma.

“Do they make as much money as engineers? No,” Mr. Crichlow said. “But not everyone wants to be an engineer, and even if the only thing you look for education to provide is an increase in wealth, going to college and majoring in the humanities is likely to vastly increase your wealth over time.”

He added that the threat of further cuts at WVU has left “a lot of uncertainty in the air, with students unclear on if their preferred courses of study will be offered and faculty members unsure if they can build successful careers at WVU.”

West Virginia University President E. Gordon Gee, who has been criticized by faculty for slashing programs instead of lobbying the state Legislature and governor for more funding, has noted a loss of trust in higher education among taxpayers.

“We simply have lost the support of the American public,” he told The New York Times in an interview last year.

The trend away from the humanities has expanded beyond West Virginia in recent months.

In North Carolina, a new law took effect in October without Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper’s signature that makes arts and humanities professors ineligible for distinguished professorships at public universities. Only STEM programs are eligible.

At the University of Wisconsin System, where enrollment fell for years, President Jay Rothman has suggested “shifting away from liberal arts programs to programs that are more career specific, particularly if the institution serves a large number of low-income students.”

More high school graduates have proven reluctant to take on the mounting student loan debt of a college degree as living costs have soared with inflation since the pandemic.

Schools have likewise found themselves competing for a shrinking pool of applicants and dwindling state funds.

Enrollment at four-year public colleges and universities fell by 3.3%, from 5,491,391 full-time students in spring 2019 to 5,308,277 in spring 2023, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

The National Education Association reported in October that 32 states spent less on public colleges and universities in 2020 than in 2008, with an average decrease of nearly $1,500 per student.

Peter Wood, president of the conservative National Association of Scholars, said a creeping emphasis on liberal politics over job skills has weakened support for humanities programs in recent decades.

“Enrollments declined as students correctly sized up what was on offer,” said Mr. Wood, a former associate provost at Boston University. “I feel sorry for the faculty members who played it straight and continued to teach good courses despite the decline of their departments. They are the collateral damage of these cutbacks.”