The House approved legislation Wednesday to add a question on citizenship into the decennial census and to change the way seats in the House are doled out, slicing noncitizens from of the count.

That would mean states with high noncitizen populations would lose clout in the House relative to other states.

The move would break with 230 years of practice.

Republicans said it was both a response to the border chaos and a way of protecting voter integrity, saying political power shouldn’t be based on people who have yet to gain citizenship and, in some cases, are here illegally.

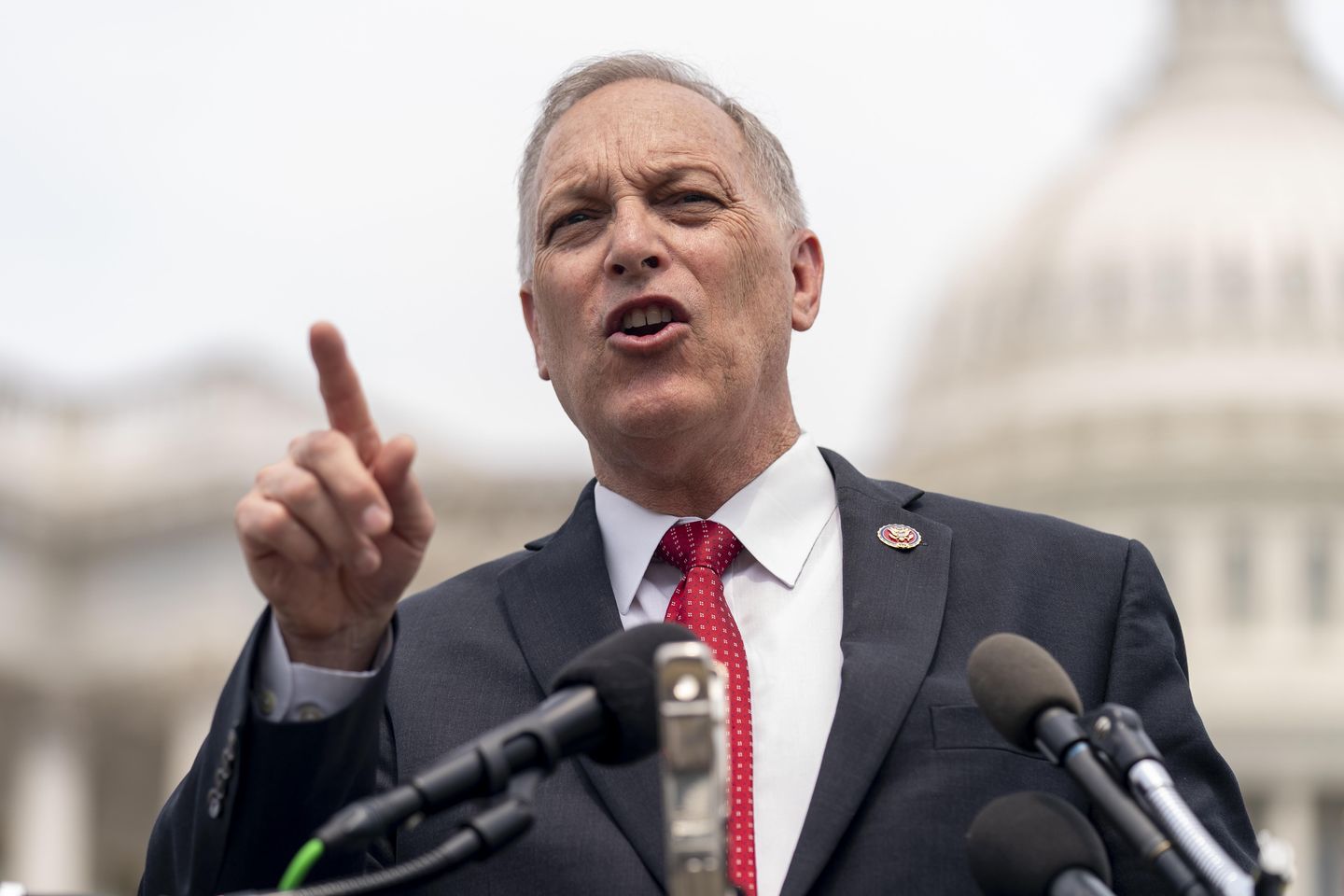

“It has distorted the population and skewed the one-person, one-vote standard,” said Rep. Andy Biggs, Arizona Republican, who led the battle for the bill.

The bill cleared on a 206-202 party-line vote. The legislation stands little chance of advancing in the Democratic-led Senate, much less getting signed by President Biden.

Rep. Jamie Raskin, Maryland Democrat, led the opposition Wednesday. He said the Constitution says seats are apportioned based on the total population. He said the Supreme Court has restated that principle in its rulings.

“We don’t need to start finger-painting on the Constitution,” he said.

Mr. Biggs, though, said the justices have signaled a willingness to let states use other measures for their apportionment.

The bill has drawn stiff opposition from the White House, which said it would not only violate the Constitution but would upend the 2030 count by making it more expensive and more difficult to get an accurate figure.

“The Biden-Harris Administration is committed to ensuring that the census remains as accurate as possible and free from political interference, and to upholding the longstanding principle of equal representation enshrined in our Constitution, census statutes, and historical tradition,” the White House said in an official statement of policy.

Left-leaning voting-rights groups complained about both the apportionment changes and the inclusion of a citizenship question. They said even asking about citizenship would scare some people away from taking part in the census, thus skewing the data.

The Constitution reads: “Representatives shall be apportioned among the several states according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each state.”

Then-President Trump tried to add a citizenship question to the 2020 census.

That effort was blocked by the courts, with the Supreme Court eventually ruling that while such a question would be legal — and indeed has been asked in past decennial censuses, and is still asked in some census surveys — Mr. Trump bungled the process for adding it into the 2020 count.

Experts say there is significant political power resting on the issue and if immigrants without documentation, or more broadly all noncitizens, were excluded it would shift seats from some immigrant-heavy states to other ones.

The Center for Immigration Students in 2019 calculated that eight states would have lost representation after the 2020 census if noncitizens were excluded from the apportionment.

Those states would have been California with three seats, Texas with two, and Florida, New Jersey and New York each with one.

The vote came the same day that House Speaker Mike Johnson unveiled separate legislation to require proof of citizenship before a ballot could be cast.

“This is very simple,” said Rep. Chip Roy, Texas Republican. “Should only citizens vote in the United States of America in federal elections? We’re going to call the question and we’ll see where they land.”

• Alex Miller contributed to this article.