The U.S. needs an urgent “whole-nation” rethink of long-held beliefs about war and peace, one of the country’s most experienced and battle-hardened Marines is urging.

“We believe that peace and war are binary and mutually exclusive states of national existence,” said retired U.S. Marine Corps Lt. Gen. Wallace “Chip” Gregson. But “the absence of armed conflict for now does not mean the absence of existential threat.”

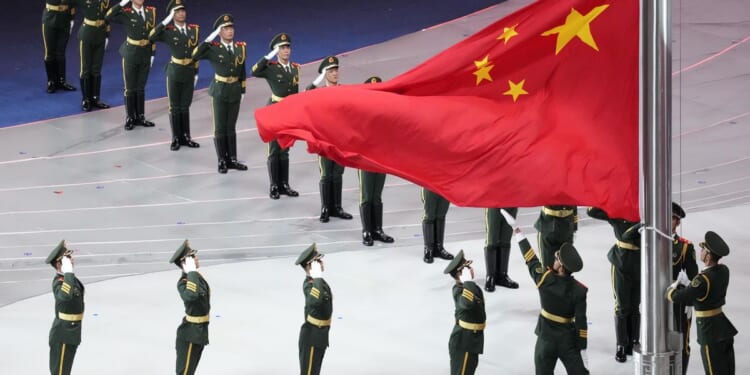

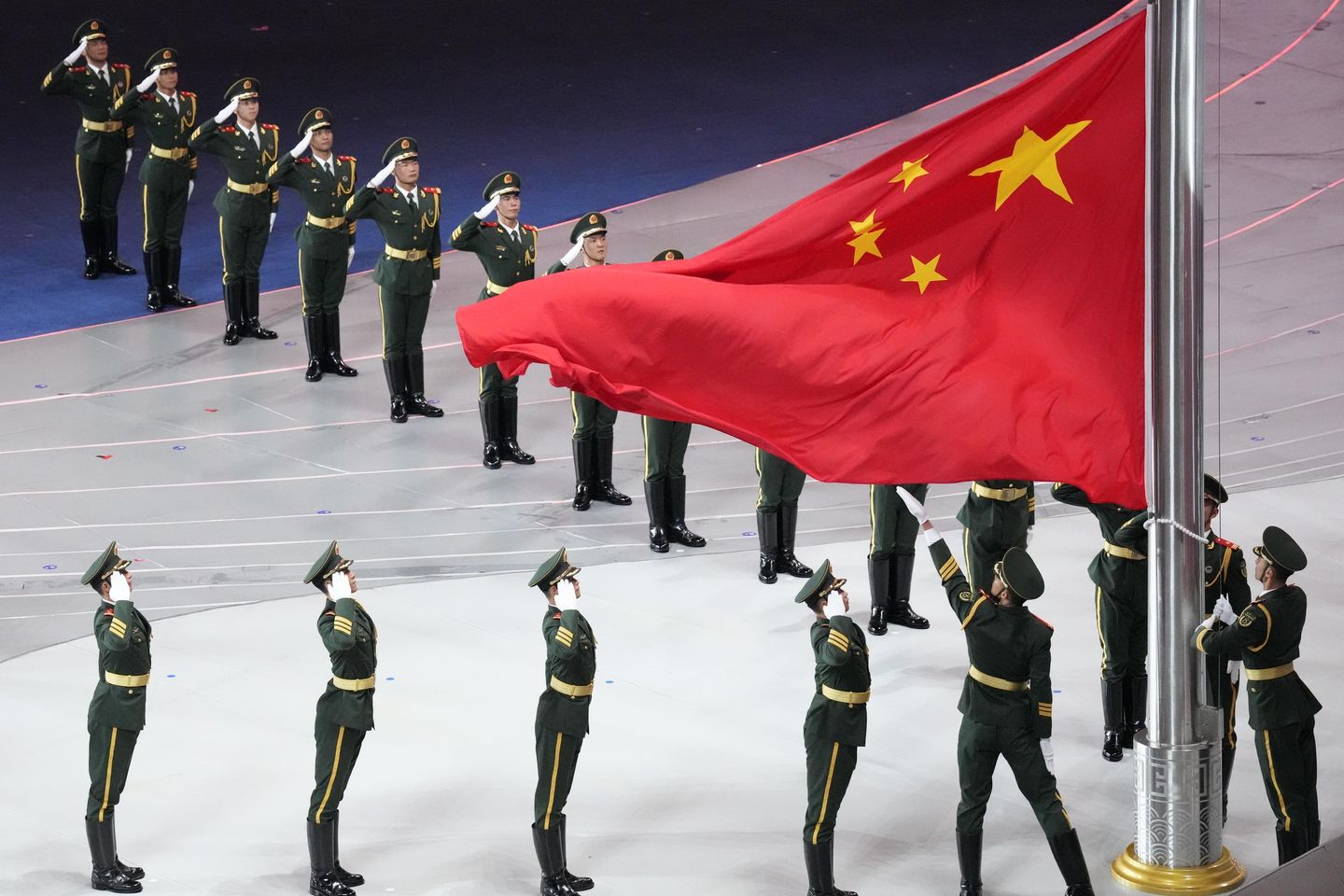

The rise of China as a military, economic and ideological competitor to the United States, combined with deepening alignments between U.S. adversaries in Beijing, Moscow, Tehran and Pyongyang as well as non-state actors, is eroding this assumption, he said.

The new strategic reality — of a multi-pronged challenge to the post-war, U.S.-led world order — is being dubbed “The Axis of Upheaval,” Gen. Gregson noted. It’s still “a fight – but not with bullets yet.”

The Marine general addressed the May 7 edition of The Washington Brief, a monthly virtual discussion hosted by The Washington Times Foundation. The theme of the session was “Policy and Strategy in an Age of Expanded Threats.”

The ex-Marine enjoys a wide perspective. His resume includes front-line combat in Vietnam and a later stint as commander of Marine Corps forces in the Pacific. He also boasts political and bureaucratic insight — he was a former assistant secretary of defense, specializing in Asian and Pacific affairs.

“The Chinese Communist Party wages a bitter information war we are losing, despite our natural advantages,” Gen. Gregson fretted. Citing China’s human rights abuses and its aggression toward regional democracies, he said, “We are not defending our own beliefs and principles.”

Internal politicking is also undercutting confidence in U.S. policy: “The delay in getting aid to Ukraine is not encouraging to our allies,” he added.

He suggested Washington gain more access to regional facilities and deploy more forces and modern weaponry to the Indo-Pacific theater. He also said it was essential to strengthen America’s military-industrial base, given that “we are decommissioning ships faster than we are building them.”

But his key message was a call for greater punch in the battle of ideas.

China is perceived to lack “soft power” — the appeal of attraction, via the kind of values that the U.S. Constitution preaches, and the kind of cultural assets that Hollywood produces so successfully. Yet, he argued, many believe democracies are losing control of the global information space.

Following financial crises and catastrophic military failures in the Middle East, cynicism and self-doubt have become embedded in Western public mindsets. This, combined with the ubiquity of social media, offers openings and channels for strategic anti-Western cognitive warfare operators to exploit.

“We must rebuild our political warfare institutions to make our case for liberal democracy and human rights, to get our message to the people of China and to make our case to our own population and our allies,” Mr. Gregor insisted. “Chinese citizens and their financial assets are leaving China, so we can win this fight, but we need to compete.”

Soft use of hard force is one viable tactic. He noted that Japanese humanitarian aid delivered by military personnel and civic groups in the wake of a typhoon in the Philippines proved to be one catalyst for changing democratic partnerships in the region.

Those changes were visible at the unprecedented Japan-Philippines-U.S. summit, held in Washington on April 11.

That trilateral was “historic” and “really significant, …a sign of changing attitudes and changing international threats,” Gen. Gregson said. “Democracies are beginning to muster and push back.”

Japan intends to double its defense budget by 2027. Recent aggression by two sitting members of the UN Security Council, China and Russia, “knocked the slats out” of Japanese confidence in the global body, Mr. Gregson told the briefing.

But hard assets will also matter in the fight.

“The Western Pacific is a maritime theater,” he said. But, “China has 350 warships; the U.S. has 290.”

Gen. Gregson cited with approval current discussions on whether Japanese and South Korean shipyards could refurbish U.S. warships. That would allow American facilities to concentrate on construction rather than repair, he said.

“We are there, but we need to be more there,” he said of the Indo-Pacific region. “We need to step up not just our physical presence, but in our ideology, in our declarations and in all those political warfare things we used to be good at but have somehow forgotten how to do.”

His views faced some pushback.

Recalling the Henry Kissinger strategy of pitting China and the Soviet Union against one another, panelist Alexandre Mansourov, a professor with the Center for Security Studies at Georgetown University, questioned the soundness of Washington’s current approach of confronting both simultaneously.

The current policy is “not driving wedges, but bringing them together,” he said.

The scholar added that Moscow’s presence in the Russian Far East is weak, hence it needs China and North Korea to cover its rear while it focuses on the war in Ukraine.

Though he conceded that the approach may have been right for its time, “the ultimate wisdom of Kissinger’s policy has yet to be determined,” Gen. Gregson responded.