HONG KONG — An appeals court on Wednesday granted the Hong Kong government‘s request to ban a popular protest song, overturning an earlier ruling and deepening concerns over the erosion of freedoms in the once-freewheeling global financial hub.

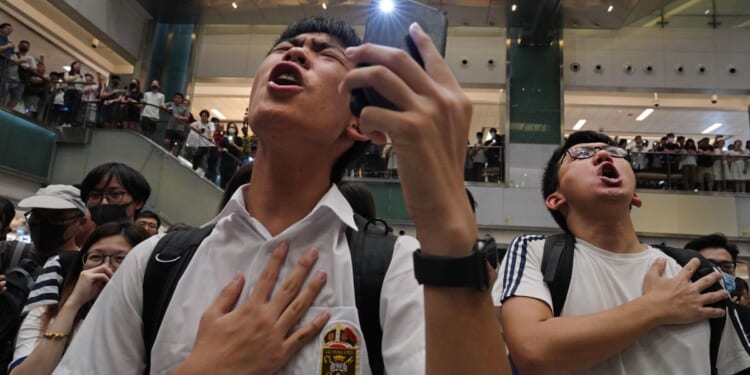

“Glory to Hong Kong” was often sung by demonstrators during huge anti-government protests in 2019. The song was later mistakenly played as the city’s anthem at international sporting events, instead of China’s “March of the Volunteers,” in mix-ups that upset city officials.

It was the first time a song has been banned in the city since Britain handed the territory back to Chinese rule in 1997.

Critics have said prohibiting broadcast or distribution of the song further reduces freedom of expression since Beijing launched a crackdown in Hong Kong following the 2019 protests. They have also warned the ban might disrupt the operation of tech giants and hurt the city’s appeal as a business center.

Judge Jeremy Poon wrote that the composer intended for the song to be a “weapon,” pointing to its power in arousing emotions among some residents of the city.

“We accept the assessment of the executive that prosecutions alone are clearly not adequate to tackle the acute criminal problems and that there is a compelling need for an injunction,” he said.

He said the injunction was necessary to persuade internet platform operators to remove “problematic videos in connection with the song” from their platforms. The operators have indicated they are ready to accede to the government‘s request if there is a court order, he added.

The ban would target anyone who broadcast or distributed the song to advocate for the separation of Hong Kong from China. It would also prohibit any actions that misrepresent the song as the national anthem with the intent to insult the anthem.

The song can still be played if it is for lawful journalistic and academic activities.

Failure to comply with the court order may be considered as contempt of court and could be liable for a fine or imprisonment.

Authorities have previously arrested some residents who played the song in public under other offenses, such as playing a musical instrument in public without a permit, local media reported.

As of mid-afternoon on Wednesday, “Glory to Hong Kong,” whose artist is credited as “Thomas and the Hong Kong people,” was still available on Spotify and Apple Music in both English and Cantonese. A search on YouTube for the song also displayed multiple videos and renditions.

Google said in an email to the AP that it was “reviewing the court’s judgment.” Spotify and Apple did not immediately comment.

George Chen, co-chair of digital practice at The Asia Group, a Washington-headquartered business and policy consultancy, said it would be most practical for tech companies to restrict access to the content in question in a certain region to comply with the order.

Chen called on the government to consider how to ease public concerns over the order’s chilling effect on free speech.

He said he hoped such bans will not become “the new normal” and establish a precedent. “This will get people really worried about how free Hong Kong’s internet will be like tomorrow,” he said.

Beijing imposed a sweeping national security law in 2020 to quell the months-long unrest. That law was used to arrest many of the city’s leading pro-democracy activists. In March, the city enacted a home-grown security law, deepening fears that the city’s Western-style civil liberties would be further curtailed. The two laws typically target more serious criminal acts.

After the judgement was handed down, Lin Jian, a spokesperson for China’s Foreign Ministry, said stopping anyone from using the song to incite division and insult the national anthem is a necessary measure for the city to maintain national security.

Hong Kong’s Secretary for Justice Paul Lam insisted the injunction was not aimed at restricting the normal operation of internet service providers. He said the government would do its best to preserve the city’s free flow of information.

Lam argued that the acts covered by the ban could be constituted as criminal offenses even before the court order, and that the scope of the injunction was “extremely narrow.”

But Eric Lai, a research fellow at Georgetown Center for Asian Law, said that even though judicial deference to the executive on national security matters is common in other jurisdictions, the court has failed to balance the protection of citizens’ fundamental rights including free expression.

“It disappointingly agreed to use civil proceedings to aid the implementation of national security law,” he said.

The government went to the court last year after Google resisted pressure to display China’s national anthem as the top result in searches for the city’s anthem instead of the protest song. A lower court rejected its initial bid last July, and the development was widely seen as a setback for officials seeking to crush dissidents following the protests.

The government‘s appeal argued that if the executive authority considered a measure necessary, the court should allow it unless it considered it will have no effect, according to a legal document on the government’s website.

The government had already asked schools to ban the protest song on campuses. It previously said it respected freedoms protected by the city’s constitution, “but freedom of speech is not absolute.”

___

Associated Press writer Zen Soo contributed to this report