One night in 1983, I wandered through the Sam Goody record store in New Jersey’s Burlington Mall in my usual quest for new albums. It was a year or two before compact discs became popular, and decades before digital downloads. It was also 14 years before DVDs, and I spotted a copy of the Beatles’ last move, “Let It Be,” on sale (for about $19.95 or so) on VHS videotape. Since I had never seen it, I thought I’d add it to my already expansive collection of Beatles albums and videotapes.

It was simply an impulse purchase. I had no idea that the movie version of “Let It Be” would soon be withdrawn from circulation by the remaining three Beatles and their business associates for the next four decades. Last month though, “Variety” reported that the two surviving Beatles and the wives of the late John Lennon and George Harrison have finally deigned to allow it to be seen once again:

For decades, the attitude toward the documentary “Let It Be” in the Beatles‘ camp seemed to be: Let it rest in peace. But the film is finally going to be seen again. A restored version of the 1970 movie is coming soon to Disney+, the same service that brought fans “The Beatles: Get Back,” the 2021 Peter Jackson docuseries that used outtakes from director Michael Lindsay-Hogg‘s original film.

The documentary will re-premiere on Disney+ May 8, certain to be a red-letter day for Beatles fans who have spent most of their lives wondering if it would ever be let out of the vault again. Not only has the 1970 film been dusted off, but it’s been restored by Peter Jackson’s Park Road Post Production using the same technology employed to make the vintage footage in “The Beatles: Get Back” look and sound as revitalized as it did.

The original film has been notorious for being the one item in the Beatles’ catalog that Apple seemed to want to suppress rather than exploit. “Let It Be” has not been officially in circulation in any form since the early 1980s, although muddy-looking bootleg copies have been widely available. Those boots were lifted off VHS and laserdisc versions that came out in the early days of the home video revolution; the movie never made it to a release in the DVD era, much less Blu-Ray or streaming.

As a diehard Beatles Kremlinologist, when I watched the last episode of “Get Back” for the first time in November of 2021, I was keenly aware that the documentary series ends almost immediately after the group’s legendary rooftop concert atop their Savile Row Apple Records office building on January 30th, 1969. But, having seen the “Let It Be” videotape, I knew that the day after the rooftop concert, the band performed complete versions of three more songs in the basement studio of the Apple building. These were the then-new piano and acoustic guitar based songs “Two of Us,” “The Long and Winding Road,” and “Let It Be.” (These songs were edited into the “Let It Be” film before the rooftop concert, so that the movie could end with – spoiler alert! – Lennon’s classic “I’d like to say thank you on behalf of the group and ourselves, and I hope we’ve passed the audition” tag line.) Thanks to the movie’s 1970 release, Lennon’s early 1969 throwaway quip ended up being his otherwise unintended summation of the career of the rock group he founded.

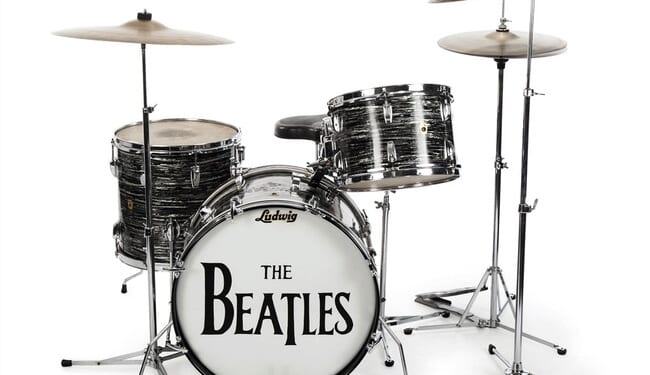

The rereleased version of “Let It Be” is framed in the original 4X3 format, unlike Peter Jackson’s “Get Back,” which may initially appear odd on modern 16X9 format TVs, but it helps to distinguish between the two projects. Lindsay-Hogg’s film begins with a pair of somber portents: the first shot in the film is the Beatles’ beloved roadie Mal Evans appearing to remove the band’s legendary “Drop-T” logo front drum head from Ringo’s bass drum (seen in the photo atop this article), an ominous metaphor of their impending breakup. As Evans and another roadie build Ringo’s makeshift drum riser in the Twickenham film studio, the camera pans to Ringo sitting by Paul McCartney playing a morose interpretation of Samuel Barber’s “Adagio for Strings.” Atop his grand piano is a mostly eaten green apple, a foreshadowing of their record company about to be devoured by the rapacious American rock manager Allen Klein, who had already added The Rolling Stones to his media empire.

This is followed by a glassy-eyed John Lennon playing one of his many rehearsals of “Don’t Let Me Down” while the omnipresent Yoko Ono looks on beatifically, followed by an early take of “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer.” This song of course, wound up on “Abbey Road,” about which John Lennon told “Playboy,” shortly before his 1980 assassination, “I hate it, ‘cos all I remember is the track. He made us do it a hundred million times. He did everything to make it into a single and it never was and it never could’ve been, but he put guitar licks on it and he had somebody hitting iron pieces and we spent more money on that song than any of them in the whole album.”

In these early jams, McCartney appears to be the only Beatle with any enthusiasm, though part of this is surely his familiar onscreen ye olde time-y show biz persona. Which lasts until his infamous onscreen fight with George Harrison over the latter man’s guitar playing. Harrison would temporarily quit the group after this painful scene was included in the “Let It Be” movie, which many believe was the reason the film has long been out of print. Lindsay-Hogg’s reaction? As he told the New York Times last month:

[In 1970] No one had ever seen the Beatles have a fight, but that wasn’t really a fight. Up to that point, no one had filmed, except in bits and pieces, the Beatles rehearsing. So that was new territory. That exchange between Paul and George, they never commented on, because it was the same kind of conversation that any artistic collaborators would have. As a director in the theater and in movies, I know that kind of conversation happens five times a week.

All of these early scenes, compounded by the somewhat murky cinematography during the early Twickenham scenes, led many (not least the former Beatles themselves) to immediately view the movie as a serious downer, a film about the greatest rock band in the world collapsing before the viewers’ eyes. (Lennon burst out in tears when he viewed “Let It Be” in its entirety for the first time in a near-empty San Francisco theater shortly after its release, at the invitation of “Rolling Stone” magazine impresario Jann Wenner.)

While Peter Jackson’s “Get Back” series made (most of) the “Let It Be” sessions seem nowhere near as gloomy as the Beatles remembered them, a certain amount of the charm of the Jackson miniseries could be the Beatles being used to donning their Hard Day’s Night and Help–era Beatlemania-era personas when the cameras were running. George Martin long spoke of the Beatles’ great collective charm and charisma as the reason why he signed them, not knowing if their musical skills would expand far beyond their initial early days.

But how did it get to this point? Ian MacDonald wrote of the filmed “Let It Be” sessions in his in his well-researched 2005 book, Revolution in the Head:

Working on ‘Happiness is a Warm Gun’ had been a special case – a stimulating challenge, but a tough one compared to idling by with edits and overdubs. Suddenly The Beatles found themselves faced with flogging through much the same process many times over. In effect, they had called their own bluff: this was too much like hard work for men with nothing to prove and no compelling financial reasons to put themselves through hoops. Unfortunately the press had been notified and a film-crew hired in to shoot the proceedings. They had to do it – or at least pretend to. Their instinctive solution was to jam sporadically, sending the whole thing up, much as they did on loose nights in Abbey Road. This time, though, the meter was running: a film studio was rented and cameras were rolling. Driven by his ingrained work ethic and assumed burden of leadership, McCartney attempted to impose discipline on this devious disorder, but the others had had enough of his pedantic [musical directing] and resented being drilled like schoolboys. (When, he suggested that they were merely suffering from stage-fright, Lennon stared at him in stony disbelief.)

The truth was that they were adults and no longer adaptable to the teenage gang mentality demanded by a functional pop/rock group. Harrison yearned to be third guitarist in an easygoing American band, Starr was looking forward to being an actor, and Lennon, who a few months earlier had been simultaneously attacked as a sell-out by the revolutionary Left and busted by the forces of the establishment for possession of drugs, wanted to break the mold completely and confront the world with outré cultural subversions in company with Yoko Ono. (Sitting inscrutably beside him throughout these dispiriting sessions, she contributed to their failure, something of which she seemed uncharacteristically oblivious.)

“Sometimes He Works With Us, Sometimes Against Us”

As “Variety” noted above, since its release in 1970, the movie version of “Let It Be” has had a rather notorious history. Its musical origins go back to the Beatles’ eponymous 1968 LP, universally known as “The “White Album,” which from its cover to most of its songs was a reaction to the psychedelia of 1967’s “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” and “Magical Mystery Tour,” albums where George Martin came to fore as the Beatles’ producer, arranger, and assembler of cutting-edge sounds. In 1968, Martin told an interviewer that the Beatles began to grate at his role in the complex productions during the “Pepper” and “Mystery Tour” era:

In a 1968 magazine interview conducted during the “White Album” sessions, Martin confessed that he no longer had the control he once did: “[In the early days] I was very much the boss and they were my pupils. They were virtually under my thumb. This naturally changed with their success and power in that today they are considerably wealthier than I am. Naturally they want more to say about what goes on. It’s a rather like the students revolting in France. Youth is realizing its power and it wants to have more to say about his fate.”

Speaking of 1967, Paul McCartney had this to say: “[George Martin] always has something to do with it but sometimes more than others…Sometimes he works with us, sometimes against us; he’s always looked after us. I don’t think he does as much as some people think. He sometimes does all the arrangements and we just change them.” As Paul later revealed to Rolling Stone, the amount of credit often given the producer was a point of contention: “The time we got offended, I’ll tell you, was one of the reviews, I think about Sgt. Pepper — one of the review said, ‘This is George Martin’s finest album.’ we got shook; I mean, we don’t mind him helping us, it’s great, it’s a great help, but it’s not his album, folks, you know.’ So you know there’s got to be a little bitterness over that.”

Additionally, by the end of 1967, there were bands such as the Moody Blues who were beginning whole careers aping the sounds that Martin and the Beatles had created in the studio. Also, whereas the Beatles’ psychedelic period was dominated by Martin’s studio trickery and massive overdubs, the band themselves were keen to return recording once again as a rock and roll group, playing, in the studio, as an ensemble, as often as possible.

The Sgt Pepper-era method for recording the band involved recording a handful of group performances, and then going to town with massive numbers of overdubs, including on the recording of “A Day in the Life,” a whole forty-piece orchestra. The “White Album” sessions largely reversed this strategy. While it became thought of among the public as the album where McCartney, Lennon and Harrison were recording solo songs, with the rest of the band acting as sidemen, several tracks on the “White Album” required dozens and dozens of takes to perfect, which had the effect of, at least temporarily, revitalizing the Beatles’ interest in being a band once again. George Harrison’s excellent song “Not Guilty” required over 100 takes – and was ultimately left off the album!

John Lennon’s “Happiness Is a Warm Gun,” with its multiple time signatures and tempo changes, required 70 takes, and was seen by the band as a key inspiration for their goal on what became initially known, in early 1969, as the “Get Back” sessions.

“We Don’t Want Any of Your Production Crap on This”

In 2012, four years before he passed away, George Martin told Mark Myers of the Wall Street Journal the difficulties these self-imposed rules forced upon on the band’s endeavor to make a new record:

MM: Where did things start to go off the rails with the album?

GM: From the start. John came to me and said, “I want to make this clear: we don’t want any of your production crap on this.” I said, “What do you mean by that?” He said, “No overdubbing. We do it live. We do it for real. We’re a good band. No additions of other instruments. None of your orchestrations. We’re a band. We’re a good band. We can do it.”MM: That’s pretty blunt.

GM: It was. John laid down these strictures. He continued, “Moreover, we’re not going to edit. All of our masters will be finished works in the studio.” This meant no splicing if there were mistakes or sound problems. If that happened, we’d have to do complete re-takes.

While Lennon, who returned to his roots as a straight-ahead rocker after his acid-fueled dalliances with psychedelia on “Revolver,” “Sgt. Pepper,” and “Magical Mystery Tour,” was initially enthusiastic about McCartney’s goal of recording a live-in-the-studio album, he was otherwise surprisingly unprepared for the project. While Paul arrived with the sketches for several songs in tow, Lennon and Harrison, each for their own reasons, were not as prepared.

In hindsight, the Beatles’ February 1968 retreat to Rishikesh India to study TM with the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi was Lennon’s last great sustained period of songwriting for the Beatles. As Ian MacDonald noted in his well-researched 2005 book, “Revolution in the Head,” “Apart from mountain air and Transcendental Meditation, the most significant thing about The Beatles’ stay in Rishikesh was that they were almost entirely drug-free. (Though they smuggled in enough marijuana for a regular evening joint, they foreswore LSD.) This undoubtedly cleared their minds and helped them recharge their batteries; indeed their creativity revived so sharply that they wrote more than thirty new songs between them.”

However, Lennon used up virtually all of the songs he wrote in Rishikesh on the “White Album,” meaning that, particularly as seen in Peter Jackson’s lengthy miniseries, for him, the “Let It Be” sessions amounted to jamming (particularly on the old ‘50s songs the band originally cut their teeth on), endless attempts at rehearsing “Don’t Let Me Down,” and rehashing his early 1968 song, “Across the Universe.” in a quixotic search for a satisfactory version.

In contrast, while Harrison had written many of the songs that would appear on his magnum opus November 1970 solo album “All Things Must Pass,” as Peter Jackson’s documentary highlights, several of these songs were tacitly rejected for “Let It Be,” because Lennon and McCartney refused to take them seriously and develop them into full-fledged completed recordings.

Lindsay-Hogg himself once said that shooting the film “began to feel like Satre’s play No Exit; characters trapped together in a room, uncertain why they were there and not knowing out to get out. There didn’t seem to be any way of stopping it.” Once shooting ceased, he submitted his original cut of “Let It Be” (still called “Get Back”) in the summer of 1969, with the intention that it was going to be a television special. However, by early 1970, new Beatles manager Allen Klein was keen to see “Let It Be” playing in movie theaters. In 2021, Lindsay-Hogg told interviewers:

“Once [Klein] got involved, he was thinking theatrical, not television, and for a variety of reasons,” including wanting to interest MGM in the release, on which Klein was hoping to get a seat on the company’s board, he says, “luring them with the Beatles movie, which he would maneuver away from United Artists – who weren’t sure they wanted it anyway. The Beatles had a three-picture deal, but UA didn’t necessarily want a documentary. But then, later, The Beatles were breaking up, and it was that or nothing for UA. And that’s partly why the release was held up, into the following year.”

Along with getting the film version of Let It Be out the door, Klein introduced Phil Spector to the Beatles to produce a viable soundtrack album to accompany it. The band knew that their “live in the studio” approach was a dead-end; they had asked George Martin to produce Abbey Road, their swan song, using all of his production and arranging skills, after the box canyon disaster of the Let It Be project. Apparently, though, McCartney never heard Spector’s massively overproduced version of “The Long and Winding Road” until it was complete, and was then unable to cancel its release. McCartney’s reaction to the Spector version of that song was one of the last mile markers on the road to the band breaking up for good.

But as depicted in the “Let It Be” movie, the songs are much closer to McCartney’s original live in the studio brief for the album. And while Peter Jackson’s team used their MAL (Machine Assisted Learning) tools to enhance the mixes in the film’s 2024 reissue, the songs still have their stripped-down appeal, unlike Spector’s lugubrious album.

“Take That, Yoko!”

Reformatting the compositions for “Let It Be,” shot for the 4X3 television screens of the day to the 1:85:1 aspect ratio of motion pictures, added to the film’s grainy, muddy appearance, a half century before Peter Jackson’s restoration efforts yielded the colorful footage seen in 2021. By the time “Let It Be” debuted in May of 1970, audiences knew the Beatles had officially broken up the previous month, and this knowledge, along with the film’s appearance, combined to sink its reputation. As did the presence of the small woman who was in many, many shots in the film:

The crowd I first saw the original film with weren’t interested in a happier spin on the Beatles. They were there to render judgment, to be the choric voice of the Beatles’ community declaring their disapproval. In other words, they were there to boo. They were there to boo Yoko Ono. If I remember the film correctly, the opening credits were barely done when we see John Lennon, and there is Yoko, sitting right beside him.

“Boooo.”

Then, there is Yoko, knitting right beside him.

“Boooo.”

For the length of the movie, every time Yoko was on camera, the crowd booed, as if to say, “Take that, Yoko, for breaking up the Beatles.”

There are two things generally remembered about the film now: the euphoric rooftop concert that closes the movie and the horrible, miserable dust-up between bossy-pants Paul and passive-aggressive George. McCartney has been trying to get Harrison to play a less-busy strumming [pattern], and does so with cringe-making condescension: “I’m trying to help, but I always hear myself annoying you,” says an exasperated Paul.

“No, you’re not annoying me,” says George in a flat you’re-dead-to-me tone. “You don’t annoy me anymore.” It is the scene that best captures the unhappiness and mutual dislike that was destroying the band.

But Peter Jackson says that such scenes did not accurately represent what was going on between the Beatles, and he has the footage to prove it.

And he did. What Jackson had compiled was, as he put in 2021, a “documentary about the documentary.” At last, viewers can see that original documentary – in an appearance that’s far more detailed and colorful than was available to Beatles fans in 1983. As one of many Beatles fans who have been calling for its release since the early 2000s, I’m happy to see the surviving Beatles “Get Back” to releasing Let It Be to the public.